Following the money in the 1876 Election Scandal Leads to a Salem bank.

By Kylie Pine

What do an $8,000 dollar check, ciphered telegrams, Asahel Bush, two Wall street brokers, Jefferson Davis’ private secretary and the United States Senate have in common? They were all embroiled in a fraud inquiry in the aftermath of the 1876 election for president. In headlines that echo in today’s news summaries, replete with phrases like voter fraud and election meddling and witnesses refusing to answer direct questions, the story of an $8,000 check deposited in Salem’s Ladd & Bush bank caught my attention this past week. There is enough material in the lengthy testimonies and national news coverage to fill a Tom Clancy novel, but I will try to stick as doggedly to the story of the $8,000 check as the four-member U.S. Senate Sub-Committee of the Committee on Privileges and Elections did during months of investigation beginning in January 1877.

Presidential Election of 1876

Let’s set the stage for this bizarre tale. It’s 1876 and the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes is running against the Democrat Samuel J. Tilden of New York. Both candidates are running on a platform of reform, seeking to counteract the corruption of then-President Ulysess S. Grant. Grant’s scandals were so bad that he had split the Republican party. Fellow Republican, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts even coined the derisive term “Grantism” and gave a speech on the Senate floor differentiating Grant’s activities from the core values of the Republican party.[1] Tilden won the popular vote and looked like he would win the electoral college except for contested returns in several states, including Oregon.

Oregon Electors

While most of the elections controversy circled around voter intimidation in the South, the issue Oregon focused on the eligibility one of their three presidential electors. National elections were conducted differently back in the 1870s. Voters voted for designated individuals (called electors) who would then cast state’s electoral college votes for President and Vice President. While they mostly voted along party lines, they didn’t have to and votes for a state could be split between candidates. Oregon duly elected three Republican electors: William H. Odell (Eugene), John C. Cartwright (The Dalles), and Dr. John W. Watts (LaFayette). The trouble started when it was revealed that Watts was a postmaster, which made him ineligible to serve as elector. State law provided that if any elector was unable or unwilling serve, the electors present at the time of the vote should fill the seat “viva voce” (a.k.a. orally). However, Democratic Governor Lafayette Grover, in consultation with the local and national Democratic party, decided to award the ineligible Watts’ certificate to the next highest vote getter — the Democrat E.A. Cronin. The electors met in Salem to cast their votes and nothing short comedy ensued. Candidates that were not elected showed up and insisted on being present. The Democratic Secretary of State gave the certificates empowering the electors to Cronin who refused to let anyone else see them. Watts, having resigned as postmaster, immediately resigned his position as elector so that his fellow Republican committee members could reappoint him to the vacancy he just created. In the meantime, Cronin went off in a corner of the same room and appointed his own committee, claiming the other two electors vacated their position by refusing to work with him. The spectacle is made even more incredible when one considers that the highest-ranking officials in Oregon Government were all subpoenaed and required to trek to Washington, D.C. (no small trip in the 1870s) to recall before the senate subcommittee every minute detail of the affair, down to where they were standing in the room. The implications were important, though, as Hayes would go on to win the presidency by a single electoral vote.

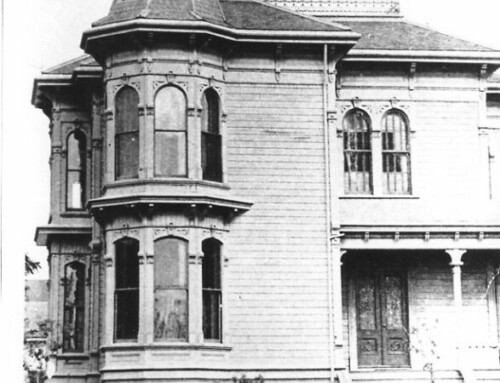

Ladd & Bush Bank at the corner of State and Commercial Streets in Salem as it looked a few short years after it made national headlines for a mysterious check it received during the 1876 presidential election. Photo Source: David Duniway Collection, Willamette Heritage Center Collections, 1999.013.0024.

Ladd & Bush Check

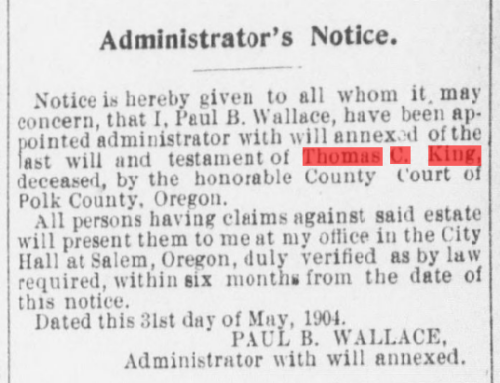

In addition to the antics of the electors, the committee also focused on $8,000 made out to Ladd & Bush Bank in Salem, Oregon. From Chicago to Memphis readers bent on reforming the corruption in Washington, watched the story of this check unfold in dramatic fashion, and Asahel Bush’s name and Salem, Oregon became national news. To summarize several hundred pages of testimony, just before the electors were to meet in Salem a check was drawn at the Wall Street Firm of Martin & Runyon and directed to the Ladd & Bush Bank in Salem via a New York agent in a cipher-encoded telegram. After a few days the funds were returned (minus telegraphic wiring fees), but the committee sniffed a rat and set out to figure out the purpose of sending these funds to Oregon. Their suspicions were probably fueled by representatives of Martin & Runyon refusing to divulge the name of the party who initiated the transaction. It also comes to light that they consulted with lawyer Mr. Burton Harrison (former secretary to Confederate President Jefferson Davis and prominent Democrat at the time), who did not have a very good reason for why he was at the sub-committee meeting with two virtual strangers. After some cagey responses by Harrison and arrests by the Senate’s Sargent-at-Arms of some key witnesses and a Senate resolution to compel the bankers and a Southern Oregon telegraphic operator to divulge information, the committee finally gets the name of the man who ordered the $8,000 transfer — William T. Pelton the secretary of the National Democratic Committee and the nephew of candidate Samuel J. Tilden. They also revealed that the money originated in a bank where candidate Tilden was a director. Not particularly good optics when running on a platform to reform corruption and nepotism.

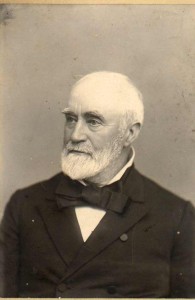

Asahel Bush. Willamette Heritage Center Collections, 0080.005.0051.02.1

When Pelton was called to testify, he laid open the purpose of the $8,000. “The reason of the thing was that there was likely to be in Oregon extensive litigation growing out of the ineligibility of one of the electors. The case was an important one…that it was proper that those gentlemen should be enabled to protect and maintain their rights in the courts.” It was then revealed that there was another $8,000 check that made its way to the Ladd and Bush Bank via San Francisco. Asahel Bush, a devout democrat, was summoned to Washington and made to testify before the committee. He doesn’t offer a whole lot of new information, confirming the funds were intended to provide legal defense of the Democratic elector, but we finally get an example of a ciphered telegram! “Sabre, cause Can Myriad be had for subject-matter if need?” which Bush does not recollect precisely, but says it generally means “Can $10,000 be had for the issue?”

The investigation lasted several months, but by March Congress had struck a deal and Hayes became the President. “The Agony Over” one headline read.[2] Despite the whiff of scandal, Ladd & Bush bank continued to prosper and stay out of the national spotlight, and after being made to reveal the secrets of the coded telegrams I would suspect they had to come up with a new cipher.

This article originally appeared in the Statesman Journal newspaper January 7, 2017. It is reproduced here with citations for reference purposes.

Citations

[1] “Republicanism v. Grantism. The Presidency a Trust; Not a Plaything and Prequisite. Personal Government and Presidential Pretensions. Reform and Purity in Government. Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, delivered in the Senate of the United States. May 31, 1872.” Published Washington: F.&J Rives & Georg A. Pailey, 1872. Accessed via Archive.org

[2] “Postscript” National Republican. 2 March 1877, pg 1. Accessed via Chronicling America.

Learn More

Read the testimony given before congress by all the players in the elections scandal in this congressional report digitized by GoogleBooks.

Read more about President Hayes and the disputed election in this exhibit by the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library.

See The Sources

1877 Testimony given before Senate Sub-Committee

1878 Harper’s Weekly Cartoon about Tilden’s Corruption Charges

1876 Election Returns breakdown for Oregon

Leave A Comment