Salem’s Chinese Americans

Chinese Americans have been living in Salem since at least 1860.[1] Despite this long presence, it has been harder to trace their experiences in the written historical record.

Sung Lung Laundry c. 1888. Located on the North side of Court street, west of Liberty Street. While this photograph of a Chinese-owned business in Salem gets used often, little discussion of Salem’s Chinatown has been had beyond popularized “underground tours.” WHC Collections 2012.049.0044.

Immigration

Most of Salem’s first Chinese immigrants, like those who came to Oregon and the West Coast in general, were from the Guangdong 廣東 province of southeast China. They spoke Cantonese and, more likely, their own local dialects. Economic opportunity in gold mining and railroad building brought many men to the West Coast of the United States.

Men who settled in Salem opened businesses like stores, medical practices, restaurants, and laundries and farmed. By 1893 there were about 250 individuals of Chinese ancestry living in Salem, or about 2% of the City’s population.[2]

Immigration to the U.S. is sometimes painted as a one-way journey. Reality is often much more complex. While some men had families and stayed in the community, many other men came for finite periods of time to work and send money to wives and family back home. Even in death, return to China was often planned for by immigrants. Cultural practices emphasizing connection to ancestors led to the disinterment and return of the remains of many men who died in Salem to their home villages in China.[3]

Read more about disinterment practices in Oregon, and Salem’s Pioneer Cemetery here.

Exclusion

Being an immigrant is hard, but being an immigrant from China was arguably harder. The 1790 federal Naturalization Act allowed only “free, white” individuals to become citizens. Individuals born in China would not be allowed to apply for U.S. Citizenship until 1943.[4]

The 1857 Oregon Constitution refused the right to vote and ability to purchase real estate or mining claims to anyone born in China.[5]

Fueled by rampant anti-Chinese sentiment, a series of federal anti-Chinese bills were passed in the late 19th century which further restricted immigration.

1875 Page Act

1875 Page Act

Prohibited recruiting labor in China and nominally the importation of women for prostitution. In reality, this law made it very difficult for Chinese women to enter the United States, creating a huge gender imbalance in the community.

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

1882 Chinese Exclusion Act

Created a 10- year ban on immigration of Chinese Laborers

1892 Geary Act

1892 Geary Act

Renewed ban on laborers and required registration and carrying of a certificate of residence. Renewed again in 1902 and made permanent in 1904.

Laws don’t always mean compliance. In Salem there was active resistance to the registration requirements of the 1892 Geary Act.[6] In 1922, George Lai Sun 黎章廣 expressed his frustration with his inability to obtain citizenship:

I have been here for so long, fifty-four years next June. I ought to be a citizen, I ought to be voting, too.[7]

In addition to the state and federal laws targeting Chinese-born Americans, local laws and practices also made life for people of Chinese heritage difficult in Salem. Ordinance No. 777 was passed in 1910, and described as needed for the “immediate preservation of the peace, health and safety of the City of Salem.” The ordinance directly targeted Chinese and Japanese noodle restaurants, requiring that they have clear glass windows or doors fronting the street and refrain from having any blinds or screens that would obstruct view of the people within. It also made it a crime to admit a minor from entering or loitering around the restaurant after 9 pm. Violations carried a minimum sentence of 5 dollars or two days in the city jail.

It was also common practice for people selling property in the Salem area to add a codicil to their deeds to prevent future owners from renting to individuals of Chinese, Japanese or African American heritage.[8]

Community

Because of the restrictive immigration policies, Salem’s Chinese American Community at the turn of the 20th century was predominantly first-generation men. Exceptions made for immigrants who could claim merchant status meant a growth in the community, including new business ventures and the setting down of family roots.

There is evidence of a wide variety of Chinese-owned businesses in the Salem area. Stores, medical practices, laundries, hops brokerages and restaurants to name a few. Stores, especially, provided connection with cultural heritage, importing goods from China that would be difficult to get elsewhere. In addition to their own lines of business, those with storefronts would often provide messaging services for those who didn’t. Descriptions of yearly festivals also describe how stores served as headquarters, collecting money to buy materials for community celebrations and the place folks would gather to share.

House Cleaned and Carpet Put down. Leave orders at 262 Liberty Street (old number) ,next door to Quong Hing’s store as I do not work at Buren & Hamilton’s Anymore. Woo Ging. Oregon Statesman 19 Sept 1905

Chinatown(s)

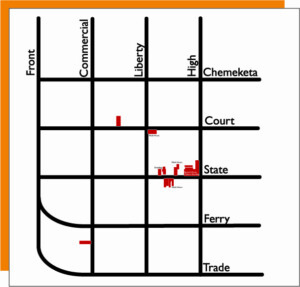

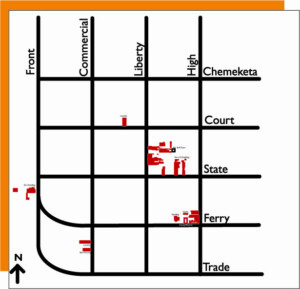

Chinese businesses and residences listed in the 1884, 1895, and 1915 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Salem, Oregon.

Chinese businesses and residences listed in the 1884, 1895, and 1915 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Salem, Oregon.

Salem’s Chinatown, was not a single, static neighborhood or block, but clusters of businesses and homes, which relocated around the downtown area overtime. The largest clusters were first centered along State Street between Liberty and High Street in the 1880s, then the east side of Liberty Street between State and Court Streets, and eventually consolidated along the northwest corner of Ferry and High Streets. The term “Chinatown” also often referred to Salem’s collective Chinese-American residents, regardless of where they were living and working.

Legally banned from owning their own property, many of Salem’s first-generation Chinese immigrants were dependent on landlords willing to rent to them. Many of those willing did little to improve the buildings they were leasing. Fire was a constant threat and water and sewer connections often far behind code requirements. These safety and health violations were often talked up in the press and used as leverage to displace Chinese American tenants from areas deemed important for future city growth and development.

The Bennett House, which stood at the northwest corner of State and High Street, started out its life as fancy hotel, but had fallen into disrepair and was one of the few places individuals of Chinese heritage could rent in the area. In 1887, a fire broke out destroying the building and killing three residents including La Fuen, Lin Yu and Ah Goon, many others, including George Sun and his wife, had to jump from the building to safety. The papers described the building as very old and hazardous and that offers had been made in the past to raze it, but the paper noted “the occupants paid the proprietors a rental of $44 per month, but the building was not worth over $1,200.”[9]

While there is a lot of newspaper coverage talking about the deplorable living and sanitary conditions in Salem’s Chinatown with titles like “Death from Dirt: The Horrible Filth in Chinese Quarters”[10] and “Sanitary condition in Chinatown condemned by Committee on Health and Police”[11] there are also stories that point fingers at the individuals who were, a contemporary mayor claimed, criminally responsible for the conditions:

Arrests will follow [Salem City] Recorder Judah reported that he had notified all owners of property in Salem’s Chinatown district to make immediate sewer connections, where such connections do not now exist, and that no reply had been received from any of the parties that are concerned. Mayor Bishop expressed an opinion that the dilatory parties should be arrested. The council has for weeks been negotiating with property owners for an improvement in the sanitary condition of this block in the business district, and the patience of the councilmen is about exhausted. After some discussion, Stoltz was successful in a motion directing Chief of Police Gibson to proceed with the enforcement of the ordinance covering the subject. If the process involved the arrest of prominent parties who persist in the maintenance of a nuisance that has been complained of, and for the abatement of which the owners have been repeatedly notified by the proper authorities[12].

In 1924, the redevelopment of the northwest corner of Ferry and High Streets wiped out the last large cluster of Chinese-owned businesses in downtown Salem.[13] A year later a newspaper columnist would claim: “Now there now is no Salem Chinatown.”[14] This did not mean that people of Chinese heritage disappeared from Salem.

Myth of the Underground Tunnels

One of the most pervasive myths about individuals of Chinese heritage in Salem is the story of subterranean tunnels. To date, no documentation has been brought forward to help prove these stories in Salem. Systematic scholarship, archaeology and oral history, however, is starting to poke holes in these legends in Salem (and across the American West) and contextualize them as a legacy of Anti-Chinese propaganda long used to justify removal of Chinese communities from lucrative downtown property. The reality is that Salem’s early Chinese residents lived and worked above ground in mostly one-story wooden structures, devoid of basements, that do not survive today.

Underground structures were used in Salem. Many early businesses used what are called sidewalk vaults, often identifiable by the glass inclusions in sidewalks meant to help light the underground spaces. These were practical places that allowed extended storage space under underutilized sidewalks and an entry point for freight deliveries that would not disrupt day-to-day activities in the retail areas above. These vaults do not have exits or connections, and the ones existing today, like those on Liberty Street and State Street, are attached to buildings that postdate documented Chinese American occupation in those areas.[15]

In contrast, the contemporary descriptions we do have of Chinese-owned business and residences in the area are consistent. The Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from the 1890s through the 1910s actually identify buildings occupied by individuals of Chinese heritage as well as color and code notations about the construction of the buildings. With one exception, all buildings labelled are wooden structures and most are only one story. [16] These are often described as shacks and ramshackle.[17] One 1891 article describes a new Chinatown being “erected from the shacks hauled away to make room for the new block.”[18] This description indicates a construction style devoid of elaborate basements or even foundations.

This is not to say that there were no nefarious activities happening. There are lots of newspaper and court documents describing opium use by both Chinese and white individuals,[19] as well as gambling[20], prostitution,[21] murder[22] and assault.[23] However, no mention of tunnels have been found in these reports to date.

Why, in the face of the evidence, do these stories persist? Lore around underground activities is often sensationalized and marketed to engaged tourists and create economic opportunities. However, spreading these stories can skew our understanding of history and the people that lived through it.

Learn more about the dismantling of the myths around some of Oregon’s most infamous underground tunnels in Pendleton, Oregon. Hidden Histories: Pendleton’s Early Chinese Community: Underground Tunnel Myth vs. Above-Ground History from Portland Chinatown Museum on Vimeo.

Outside of Chinatown

Many people of Chinese heritage in early Salem didn’t live or work in Chinatown. Farmers and farm laborers lived and worked in rural areas around the city. Some individuals took work as cooks or servants, living inside the homes of Euro-American families. A large number also came to Salem from other parts of the state due to incarceration in state institutions like the Oregon State Hospital and the Oregon State Penitentiary.

The 1900 U.S. Census enumerated 50 individuals of Chinese heritage living in Salem, but as one newspaper commented:

It would appear from the number of [Chinese] seen on Salem’s streets almost daily, that the number residing in the city exceeded fifty but it is explained that many reside on farms surrounding Salem…

Salem’s Ng family spent most of their time in Salem living and working outside of Chinatown. Ng Lung Chung (also known as Gong), settled in the Salem-area in about 1886.[24] A skillful farmer, he rented land in West Salem and South Salem where he raised hops and vegetables.[25] In 1910, the family, consisting of wife, Dora, son Charlie and daughters Alice and Helen was living on a hop farm on Slough Road (later renamed Riverside Drive) with six single men field hands from China, Korea and Kentucky.[26]

In 1910, the Ng family purchased a house at 305 18th Street. As a first-generation Chinese immigrant, born in China, head of the family Ng Lung Chung was not allowed by Oregon law to own real estate, so the deed was put in name of his eldest son — who was 12 years old at the time of purchase. Being born in the U.S., Charles H. Chung (A.K.A. Harry Ng Mun Gate), was a citizen and eligible to own property. The family sold the property in 1928.[27] Daughter Helen Ng Mung Tayne remembered the house as: “a white house with a great big maple tree in front.”[28]

Beatrice Crawford Drury, who grew up on Brown’s Island (now part of Minto-Brown Island Park, recollected that 300 individuals of Chinese heritage worked on truck farms there during her childhood.

Celebrations

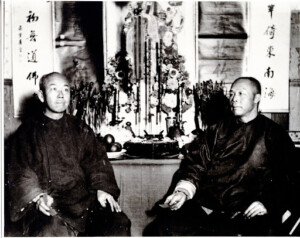

1897. Two Chinese gentlemen dressed in Chinese apparel sit in front of panels or hangings decorated with Chinese art (shrine). They are identified as Dr. Kum on the left and George Sun on the right. Mr. Sum is a merchant. They both hold Chinese calling cards in their hands. Willamette Heritage Center Collections, 2015.025.0021

At the turn of the 20th century, portions of Salem’s downtown would undergo a transformation in late January or early February. Decorations and flags would festoon shop windows and alleyways around Chinese-run businesses and the quiet night air would pop and sizzle with firecrackers – all in celebration of the Lunar New Year. The celebrations often drew crowds of onlookers from a variety of different backgrounds.

Read more about Salem’s Lunar New Year Celebrations here.

We also know from oral history interviews and archaeology that Salem’s residents of Chinese heritage celebrated the annual Qing Ming festival at Salem’s Pioneer Cemetery. As Suie Lai Sun remembered in an interview with Keizer Historian Ann Lossner:

Archaeological excavations in 2017-2018 have helped to uncover the remains of an altar or funerary table used in the Chinese section of Salem’s Pioneer Cemetery. The low concrete table is located in the northeast side of the cemetery. Used historically for funeral rites and other celebrations, the altar is one of the few remaining places associated with Salem’s early Chinese community. It had fallen into disuse by the 1950s, and photographic evidence shows it was severely damaged sometime after 1963. Archaeological investigation undertaken by the City of Salem and many community partners helped locate and uncover the altar and many associated artifacts including the grate for a burner and glass and ceramic fragments from foodstuffs that were used in rituals at the site.[29]

With the altar uncovered, a Qing Ming ceremony was revived in 2018, and it has become an annual event. Learn more about the Qing Ming festival here.

Into the Future

The dismantling of Salem’s Chinatown areas in the 1920s did not mean, that everybody of Chinese heritage left the city or that immigrants did not continue to enter the country.

Credit Statement

Written by Kylie Pine with assistance from Dr. Myron Lee, Dr. Juwen Zhang, Kimberli Fitzgerald, Kirsten Strauss and Ellen Eisenberg.

Learn More

Sources

[1] See 1860 US Federal Census which lists two Chinese-born men living in Salem and working as washers and ironers. They are named in the census as Tyron and Jurong with the surname “Chinaman.”

[2] Minor Civil Divisions 1890 Census Table Five accessible here: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1895/dec/volume-1.html

Gives Population numbers for Salem Precincts (East, North, Salem, South Salem)

East Salem –4749

North Salem – 2145

South Salem – 1691

Salem 1885

Total:10,470

1893 – Article Weekly Oregon Statesman “Chinese New Year.” Weekly Oregon Statesman 17 Feb 1893 pg 11. “There are fully 250 Chinese residents in Salem and today will be a gala day for them.”

CONCLUSION: ~2.9% of the population. (250/10470)

Concerning the Census: Oregon Statesman 09 Jul 1890 pg 4

Discussion of enumeration districts. Estimates city population about 4-5000, but if they were to do all four districts more like 15,000. Doesn’t match data given by 1890 Census with clear enumeration districts outlined.

“Oregon’s Counties” Oregon Statesman 29 Oct 1893 pg 7

Gives Marion County population as 22,454 total county!

1893 Salem City Directory –

“By the United States census of 1880 the city had 4,100 people. The same census for 1890 included the entire election precincts of which the city forms a part, and that gave 10,470.*** We estimate the population on the first of January, 1893, at 15,000 in round numbers. We arrive at this estimate taking the number of the names in this city directory for Salem and multiplying them by 3 /58 to include the wives and minor children whose names do not appear in a directory. That is the average multiplier for cities of this character. This makes 13,456. To this may be added the average of inmates of the various state institutions located here, and the population is above our figures…So that 15,000 is believed to be a conservative estimate.

***Same number as I independently calculated from Census tables (see note above)

1900 US Census 4258 city population

https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1901/dec/vol-01-population.html.

[3] Sources:

- See research reported on in OHQ: Chinese Diaspora in Oregon Special Issue (Volume 122 Number 4). Referencing Salem Pioneer Cemetery Records, oral history with Suie Lai Sun, Oregon Chinese Disinterment Documents, SARC.

- Look at census data for married/single/widowed men in Salem (1870-1910).

- Specific examples: Lai Yick, returned to China. “Dr. Lai Yick Sends Xmas Greetings to His Friends Here; Chinese Progressing.” Capital Journal 28 Dec 1928

[4] 1790 Naturalization Act only allows naturalization of “free white person[s], who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for a term of two years.” See actual text of legislation here: https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/exhibitions/artifact/h-r-40-naturalization-bill-march-4-1790 (via US Capitol Visitor Center exhibit identified as House Resolution 40 dated 4 March 1790). Not repealed until the McClarran-Walter Act of 1952. https://immigrationhistory.org/item/immigration-and-nationality-act-the-mccarran-walter-act/:

SEC. 311. The right of a person to become a naturalized citizen of the United States shall not be denied or abridged because of race or sex or because such person is married. Notwithstanding section 405 (b), this section shall apply to any person whose petition for naturalization shall hereafter be filed, or shall have been pending on the effective date of this Act.

The Chinese Exclusion Acts were repealed in 1943, allowing Chinese-born Americans the ability to naturalize for the first time. See: Act of December 17, 1943, “An Act to Repeal the Chinese Exclusion Acts, to Establish Quotas, and for Other Purposes.” (57 Stat. 600; 8 U.S.C. 212a). Instigation for this change in policy came largely from the allyship of China during WWII. Read more: Edward Bing Kan: The First Chinese-American Naturalized after Repeal of Chinese Exclusion

[5] 1857 Constitution of Oregon (enacted 1859) Article XV, section 8: “No Chinaman, not a resident of the state at the adoption of this constitution [1857], shall ever hold any real estate, or mining claim, or work any mining claim therein. The Legislative Assembly shall provide by law in the most effectual manner for carrying out the above provisions.” See Also (voting rights) 1857 State Constitution; Article II Section No. 6 “No Negro, Chinaman, or Mulatto shall have the right of suffrage.”

[6] “Didn’t Register.” Oregon Statesman 18 April 1893 reports the Chinese-born citizens of Salem did not register with the deputy sent to do the registration. Salem residence did eventually comply.

[7] Hal Patton’s Anniversary Program. WHC Collections: .

[8] See example – Abstract of Title for the Oaks Addition in Salem. Language was added to the 1910 deed that stated: “nor shall the same or any part thereof be in any manner used or occupied by Chinese, Japanese or Negroes except that persons of said races may be employed as servants…”

[9] “A Big Blaze.” Weekly Oregon Statesman. 21 Jan 1887 pg 3; “The Bennet House Fire.” Oregon Statesman 16 Jan 1887 pg 3 ;

[10] “Death from Dirt.” Evening Capital Journal 04 Apr 1890 pg 1

[11] “Action at Last.” Oregon Statesman 05 Oct 1904 pg 1

[12] “Arrests will follow” Capital Journal 07 Jan 1903 pg 4

[13] “Stroke proves fatal to Chinese Merchant.” Oregon Statesman 23 Aug 1925 pg 1. “Hop Lee’s first laundry was located on South Commercial across from the present site of the Marion hotel. After being in this location for nearly 15 years, Hop Lee moved to a building on Ferry street. Several years ago he was again forced to move because of the erection of modern structures.”

The building on the northwest corner of Ferry and High Streets that now stands was built in 1924 – essentially gutting the area round the Chinatown located in that area.

“Modern Business Block Replaces Chinatown.” Capital Journal 26 Jan 1924 pg 8.

“One story brick business block of nine store rooms to be built for the John Hughs company at the corner of High and Ferry Streets. Wrecking of the old wooden buildings are now underway…”

“Striking for a Wage.” Capital Journal 23 Ap 1924 pg 5

…the Hughes estate property at the corner of High and Ferry streets where the famous Chinatown was once located.”

[14][14] “Stroke proves fatal to Chinese Merchant.” Oregon Statesman 23 Aug 1925 pg 1. “now there is no Salem Chinatown. Perhaps 30 is a total of the city Chinese population at present.”

[15] The sidewalk vault at 148 Liberty St NE. is attached to a building that was constructed in 1915 (see Marion County Assessor’s Records profile for building giving build date here https://mcasr.co.marion.or.us/PropertySummary.aspx?pid=589135&taxid=). Compare that to the 1915 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for the area which lists Chinese-occupied buildings. None are listed at that address or proximity.

[16] See Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for 1884 (Library of Congress), 1895 (Library of Congress) and 1915 (Willamette Heritage Center).

[17] “Chinatown Condemned.” Oregon Statesman 21 Jan 1903 pg 3; “Beginning of the End.” Oregon Statesman 23 Jan 1903 pg 6; “To Remove Eyesores.” Oregon Statesman 22 Sept 1904 pg 1

[18] “General Building Notes.” Oregon Statesman 24 Sep 1891 pg 4

[19] Opium dens said to thrive in Salem. Capital Journal 19 June 1913

[20] “Local and General News” Capital Journal 24 March 1888 pg 4

Trouble in Chinatown

A Game of Dice Ends in a Fight – one Warrant for Arrest and Two for Gambling, the Result.

This afternoon Same Dick, the rather intelligent Chinaman who works for E.P. McCornick, and Jim Chung, proprietor of one of the China houses on Court street, got into an altercation over a game of dice in Lee Hay’s lodging house on State Street. It appears that Sam Dick won five cents from Chung which the latter refused to pay. Sam Dick insisted so strongly on the payment of the nickel that Jim became enraged, and picking up a large porcelain bowl which was conveniently near, broke it to pieces and hit Sam over the head with one of the largest pieces, inflicting a large scalp wound, from which the blood poured forth in streams. Jim Chung immediately got up and dusted in the direction of the depot and Sam Dick went before his honor, Recorder Strickler, and swore out a warrant for his arrest on charge of assault and battery. It is understood that warrants are also out for the arrest of both the heathens for gambling. Marshal Ross is now looking for Jim Chung and will probably find him this evening.; Chinatown Raided. Oregon Statesman 25 Jun 1893 pg 5

Two Celestials, who were running a lottery, gathered in.

Last evening about 10 o’clock Chief of Police Minto, Captain Dilley and officer Gibson made a raid on a lottery game run by Sing Hong and Sing One in the red brick building on Liberty street, and arrested both the gamblers and captured the entire outfit, consisting of tickets, several bowls, a tin pan, a table board and some $10 or $12. They were taken before Judge Edes and given a preliminary hearing. They pleaded not guilty to the charge of running a lottery and were held on $250 bonds each to appear Monday at 2 o’clock for trial. Geo. Sun and Hong Lee went on their bonds and they were released….

[21] “Chinese Fragrance.” Capital Journal 02 Sept 1893 pg 4 “…That part of the city known as Chinatown, centrally located in the Capital City, is a fruitful source of disease and moral degradation and is becoming a menace to those owning property or doing business in that vicinity. Within easy stone throw are three Chinese or Japanese houses of prostitution besides one conducted by American demimonde.”

[22] “Excitement High in Chinatown.” Oregon Statesman 25 Oct 1894 pg 4

A disturbing spirit said to be among Salem’s peaceful Celestials – the Trial Yesterday

There was a good deal of excitement among the Chinese residents of this city yesterday, the occasion being the preliminary examination of Lueng Kong on a charge of murderous assault on Loow Ging with a hatchet last Saturday night. The feeling among them is intense and the hatred felt by the friends of Ging is not so bitter against Leung Kong as it is against Joe Wan, one of the shrewdest Chinamen ever known here, who is claimed to be the real author of the crime, the man who sent for Kong and paid him to get away with Ging.

[23] “In Recorder’s Court” Oregon Statesman 05 Feb 1889 pg 4

The sweet scented Shackelford was before Recorder Conn yesterday for arraignment, after which an adjournment of the further hearing…In the afternoon the case of Ah Dock was called, for assault on Ab West , and a jury trial demanded by P.H. D’Arcy, attorney for the defendant.

The following citizens were sworn in to try the case and after patiently listening to its pros and cons, retired for a verdict: Amos Strong, E.T. Albert, J.S. Hawkins, H. Kroft and Thomas Townsend. Their deliberations lasted about two hours and resulted in a verdict of acquittal which was a source of great rejoicing in Chinatown. The case was ably handled by counsel, Goerge G. Bingham representing the state and P.H. D’Arcy the defense.; “Case Settled.” Oregon Statesman 10 Mar 1887 pg 3

The trouble between the two Chinamen Joe Dock and Ling the former of whom was arrested for assault on the latter, was amicably settled yesterday and the charge of assault against Joe Dock was dismissed from Justice O’Donald’s court. Grim visaged war has withdrawn his fierce countenance and white winged peace has settled like dove over Chinatown.

[24] Chinese Exclusion Act Case File for Ng Lung Chung. National Archives and Records Administration. Note Ng Lung Chung went by many names including Gong, John Gong and Ung Lung Chung.

[25] Ibid.; “Fine Hop Yield.” Morning Register (Eugene) 08 Sept 1910 pg 8;

[26] 1910 US Federal Census. Liberty, Marion, Oregon

Slough Road

Chung, Ng Lung, Head 50 M1 13 years China, Farmer, Hops, and Vegetables

Dora, wife, 28 M1 13 years 3 children, 3 living, Washington

Charlie, 12, Oregon

Alice, 10, Oregon

Helen, Daughter, 4, Oregon

Fred Sing, 35, boarder hop yard as are all the boarders

Yip Yuen, Boarder, 50

Six Ket Choi, Korean, 25

Leong Sue, Chinese66

Leong Fook, 66 Chinese

Abram J. Pruitt, White, 60, Kentucky

[27] 1910 Purchase 305 18th St S. –See Marion County Deed book 116 pg 35. Put house in the name of son Charles H. Chung.; 1928 – 18th ST House sold to Walter Lehman by Dora Chung. See Marion County Deed Book 198 pg 75(Lot 9 Block 9 Capital Park Edition). Sold 14 May 1928 . LINK

[28] Interview in Chinese Exclusion Act Case File for Helen Ng Mung Tayne. National Archives and Records Administration.

[29] The Public History of Cemeteries: https://publichistoryofcemeteries.org/case-studies/the-chinese-shrine-at-salem-pioneer-cemetery-a-case-study/; City of Salem Archaeology project page: https://www.cityofsalem.net/government/shaping-salem-s-future/plans-projects/salem-pioneer-cemetery-chinese-shrine-project