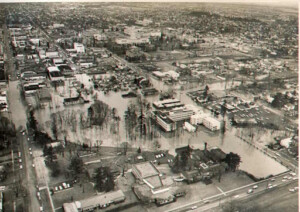

Christmas Week Flood Brings Major Flooding, December, 1964

1964, Aerial photo showing extent of Christmas flood, December 1964. Mission St. in foreground, church St. at left. Foreground, Church St. at left. Foreground Oregon State Blind School. Salem Hospital right center. Capitol and State office building in background., WHC Collections 1998.010.0018

The 1964 “Christmas” flood followed the pattern familiar in Salem history: near- record snowfall followed by record amounts of rain. Snow and freezing temperatures early in the month gave way to warm temperatures and unrelenting rain – all within a 48-hour period, Salem received four inches of rain. Accumulated snow melted quickly and, with the rain, created heavy runoff which swelled the Willamette and its tributaries. By December 22nd, the Willamette was rising at the rate of three inches per hour at Salem. Basements in the City, including that of City Hall, were flooding, and storm drains were clogged with chunks of ice and snow. The pressure of the water rushing through the sewers sent “gushers” shooting out of manholes and drains. Shelton Ditch and Mill Creek overflowed their banks, and control dams on both were working at full capacity.

Salem’s main source of water at Stayton Island was flooded, but auxiliary water supplies were holding up. Highways in and around the City, including Interstate 5, were closed in places by high water. Still, at this point, Salem’s flooding was not considered serious. The River was expected to crest at 27 feet, seven feet above flood stage, and recent dike work was expected to prevent flooding at Keizer, thought to be the area most vulnerable to high water.

All that changed on December 23rd. The Willamette crested at 30 feet and stayed there for about three hours before dropping off slightly. More than 300 Keizer homes were flooded by the raging Willamette, and the National Guard, crews of local firemen, and sheriff’s deputies used helicopters, boats, and even amphibious vehicles to evacuate more than 1,000 residents from their sodden homes.

John Erickson, 1964, Image of man with nametag reading “Penrod” carrying infant through ankle deep water in front of the Salem Memorial Hospital. The National Guard was called out during the “Christmas Flood” of 1964, shown here helping to move patients from Salem Memorial Hospital on December 23. Oregon Statesman Photo, WHC Collections 1998.010.0050

National Guardsmen also helped evacuate 121 patients from Memorial Hospital (formerly Deaconess), which again suffered for its proximity to Pringle Creek. Despite pumping and sandbagging by Oregon Correctional Institute crews, who worked through the night, dikes around the Hospital were overrun by the creek, and the basement quickly filled with water. According to a Hospital official, the water rushed in and rose thereafter at the rate of a foot an hour, until six feet of water stood in the basement. At 7:30 a.m., a decision was made to evacuate patients to Salem General Hospital, and the operation was completed in two hours, with no complications. One premature baby was removed from the hospital in its incubator; two other babies were less than three hours old, but there were no problems. Other medical buildings and homes along Pringle Creek, including an apartment complex, were also flooded.

Salem’s new $3 million sewage treatment plant was disabled by floodwaters, and, although it remained structurally sound, raw sewage began flowing directly into the Willamette River. This happened at other locations along the river as well, creating a major health threat. The State, armed with supplies of typhoid vaccines, braced itself for problems, but fortunately no epidemic resulted.

Boise-Cascade, Salem, was also hard hit by the floods again. At the plant on Commercial Street, water filled the basement, and 500 people were put out of work when the plant was knocked out of operation. There was considerable damage to equipment at the plant, and logs in the river were broken loose by raging waters. Part of a chip pile was washed away.

Downtown businesses suffered when flood waters hit with little advance warning. According to one business manager, as late as 11:00p.m. the night before, the water level seemed to have dropped, the danger past. But between 3 and 4 a.m., the waters suddenly rose in a “wave” while employees tried in vain to save what they could. Some businesses reported up to 30 inches of water; at West Coast Grocery, stores of food were lost to flood waters. The 7-Up bottling plant at 402 Church Street reported water 4-1/2 feet deep, equipment and trucks underwater, and vats of citric acid polluted by flood waters. A boat was needed to recover records from the welfare offices, where waters were waist-high.

Agricultural losses in and around Salem were high as well, due in part to the fact that the ground had not been able to thaw before the floods hit. The ground, unable to absorb even a normal amount of rainfall, had its thawed upper layer washed away in the flooding. This meant a permanent loss of topsoil to the rich agricultural lands around Salem; Marion and Polk Counties suffered some of the most severe damage in the State. In addition, farming and irrigation equipment and fences were washed away or damaged. Drainage ditches and newly planted crops were destroyed. Flood-caused erosion was heavy. In Marion County, agricultural damage exceeded $10 million.

In West Salem, a 35-man crew built 100 feet of dike between Musgrave Avenue and the railroad track but, by Christmas Eve, water was seeping through the barrier. West Salem’s main intersection, at Wallace Road and Edgewater, was under three feet of water on Christmas Eve. The river was 4-1/2 feet above Edgewater Street. Residents went without water for a short time after a 24-inch water main on the Marion Street Bridge was hit and broken open by a log on the River.

And in South Salem, a small plane carrying three men crashed about two miles south of McNary Field. The trio on board included a Salem pastor and two friends who had gone up to get a view of the flooding; all three men were dead at the scene.

On Christmas Eve, Salem received about a half-inch of rain, and Christmas Day brought another wave of heartbreak as the River crested a second time, at 29.5 feet. Evacuees crowded the Red Cross shelter in Salem, where volunteers and local business people helped Santa Claus bring gifts to displaced children.

The Capital Journal newspaper noted that, without the seven flood control dams on the Willamette River, the River would have crested at 37.5 feet at Salem rather than 30 feet. Even still, the Christmas Week Flood was the worst flood of the Twentieth Century, with damages exceeding those of the Columbus Day Storm. Governor Mark Hatfield declared the entire State an emergency disaster area, and called the flooding, “the worst disaster ever to hit the state.”

Compiled and written by Kathleen Clements Carlson

Bibliography:

Oregon Statesman, December 22-27, 1964

Capital Journal, December 21-27, 1964

Capital Journal, January 4, 1965

Taylor, George and Raymond R. Hatton. The Oregon Weather Book: A

State of Extremes. Corvallis: Oregon State University, 1999.

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment