by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

Following its consideration of the war from yesterday, the following editorial in the Oregon Statesman discusses “Flags and Accidents:”

Here are the essential facts which should never be lost sight on in considering our relations with Great Britain and Germany:

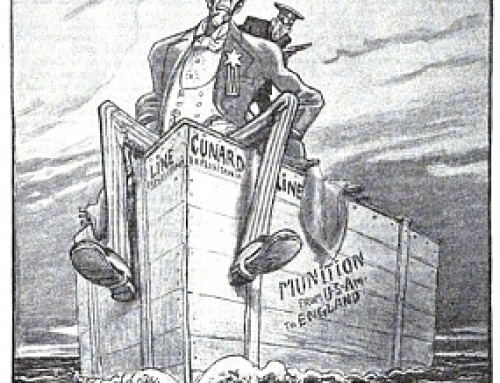

As regard Great Britain – We have no legitimate grievance against her because of the occasional use of our flag to protect one of her ships in an emergency. All modern nations have used this subterfuge. International custom sanctions it, and any law that might be enacted against it by the United States alone would have no force. But we may properly object to the abuse of the privilege. We cannot permit the British government to authorize or sanction a general and systematic use of our flag.

As regards Germany – Whether sailing the open sea or “running a blockade,” all non-combatant sailors and passengers are protected by international law, and such protection applies with special force to neutrals. The German navy has a right to stop any ship of commerce and compel it to show its papers. If the vessel belongs to an enemy, the Germans may properly seize or sink it; but they are required to save the lives of the sailors and passengers. If the vessel proves to be neutral – for example, American – the Germans must not harm it, although they may seize a contraband cargo. And, above all, they are required by the law of nations to respect the lives of those aboard neutral vessels, just as they would respect them on neutral soil. A submarine has no rights that re not common to other warships. If she cannot take the crew and passengers off a doomed vessel, then she must not destroy that vessel.

A merchant ship, however, must stop when warned. If it tries to run away, any German warship is justified in sinking it without further formality, precisely as a German submarine recently attempted to do when a British ship flying the Dutch flag showed it heels when ordered to stop. As for “accidents,: due to a failure to verify, or honestly try to verify, the nationality of a ship before sinking it, neither the United States nor any other neutral nation could tolerate them without sacrificing its sovereignty and its self respect.

The submarine was a technologically advanced weapon of war utterly unsuited for operation on the surface. The principles of principled warfare put the submarine at a disadvantage if it attempted to comply with the standards that would apply to a dreadnaught. Should a submarine have the temerity to surface and seek to enforce it right to search it would have done so at extreme risk. Parlous seas and the risk that the vessel being questioned might be armed made surface warfare by a submarine nearly impossible.

In another editorial the Oregon Statesman reprints an article from the February 10th New York Times:

WAS SOLL ES BEDUEUTEN?

Our people are struggling and offering sacrifice for the emperor and the empire, for its existence and its future, and these things cannot be sacrificed to moral superstitions. What have we in six month achieved with our noble-spirited conduct of war? Calumnies and hatred and bitter hostility everywhere – Hamburger Nachrichten.

That is a very remarkable utterance for a German newspaper of the importance and high standing of the Hamburger Nachriten. What does it mean? For one thing it means, for it plainly says, that the Germans are no longer victims of the delusion that the world outside the circle of the belligerent nations is with them. “Calumnies and hatred and bitter hostility everywhere.” Some calumnies doubtless, for they are naturally bred of the passions of war. But no hatred of the German people, no bitter hostility to them.

* * * *

Outside of Germany, German imperialism has no friends that we are aware of, and the German militaristic spirit and ambitions are viewed with deep disfavor.* * * *

Six months of war with no result save “calumnies and hatred and bitter hostility everywhere” is enough to dishearten the German soldiers and the German people. There have been other results. Germany has brought upon itself not alone the condemnation of the civilized world outside, but sore distress and privation within the empire. The proofs of it are too numerous to be ignored, and they are multiplying rapidly. Not only is there no relief in sight, but it seems to be certain that conditions will become worse. They may become quite unendurable. Shortage of food is disclosed y recent government orders; shortage of army supplies and ammunition is all too plainly indicated. Germany is like an invested fortress. Communication with the outside world must shortly be re-established or the inevitable end of the struggle will come plainly into view.According to military prognostications the German people may have an opportunity to end the war some time in the early summer . . .

The New York Times editorial goes on to lay out how the end of the war could occur during 1915. The war did not end in 1915 and it did not do so because, while few expected war and even fewer wanted war, most of the belligerents eventually accepted the reality of war because they came to believe it to be defensive. The article and the editorial illustrate that disillusionment with the war had set in, but (and this is important) once convinced that ‘their war’ was defensive, belligerents fought it with determination.

That what was being defended was an illusion became the tragedy of the balance of the years that have followed.

Leave A Comment