Flax

Flax Field, sheaves of flax in field. Storage shed in background. Possibly Oregon State Prison at right of sheds. Prisoners worked raising flax., WHC Collections 1998.010.0027

Although flax was introduced in Oregon as early as 1844, it wasn’t until 1867 that the first mill was built in Salem by Joseph Holman. Holman’s Pioneer Oil Works began operation that year at the present site of the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill on 12th Street. Oil was expressed from the flaxseed, and the by-products were returned to the growers and used for cattle feed. The tow, or flax fiber, was used for upholstery. The business became unprofitable because of lack of a consistent supply of flaxseed and soon closed. Flax grown in other areas of the state won bronze medals at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876 and the Paris Exposition of 1900.

In 1902, Mr. Eugene Bosse, who was from Belgium and grew up in the flax-fiber manufacturing business, came to Salem at the request of a large linen trust in the East. After completing some experiments, he concluded that Valley-grown flax was equal to that grown anywhere in the world, including Belgium, Ireland, and Russia. The trust was not pleased with his conclusion, and he soon severed his connection with them.

He demonstrated to local farmers that there was more money in raising flax than wheat or grain, interested investors in his efforts, and secured the lease of a farm near the State Hospital in Salem. The U.S. Department of Agriculture supplied him with seed from Russia, Belgium, and Holland. In 1903, a USDA botanist judged local fiber to be of better quality than that grown in the Mississippi Valley, and that the soil here would produce fiber comparable to that imported from foreign countries.

Mr. Bosse lost thousands of dollars worth of machinery and crops in the following years from fires which were set at his barns and storage sheds. The Sheriff felt that, rather than being a strike at Mr. Bosse personally, the fires were meant to cripple the budding flax industry and discourage others from attempting such an enterprise. The linen trust in the East was believed to be behind both the fires and other earlier efforts to thwart the Oregon flax industry.

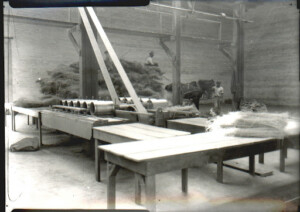

Handling Flax. Belts and tables in foreground. Loaded wagon, horses and handlers in background. Salem Public Library MJON 0109, WHC Collections 1999.003.0014

In 1915, a large-scale flax plant was begun at the State Penitentiary to give employment to idle inmates at the prison, and use their manpower to develop a crop and industry which would help Oregon prosper. The plant would also make available processing and marketing facilities for local growers, and provide leadership in the development of the industry. Unfortunately, they also suffered disastrous fires which wiped out their gains.

Other linen manufacturers in the Salem area in the 1920s included Lord and Wallace and Oregon Fibre Flax in Turner, Oregon Fibre Flax at 132 North Liberty, Miles Linen Company at 2150 Fairgrounds Road, and the Oregon Linen Mills at 1465 Madison. World War II brought an increased demand as production in Europe was interrupted, and more flax plants were developed up and down the Willamette Valley.

Oregon Flax Textiles, a division of National Automotive Fibres, had a West Salem plant which manufactured a rug product. They used flax tow which had, in previous years, been burned. Although Oregon was the only state in the Union that grew fiber flax commercially, most of it was used for such unglamorous products as ropes, twines, thread, nets, fishing tackle, mops, rugs and toweling, and defense materials.

Developments at Oregon State University reduced the harvesting and processing costs of flax, but a main obstacle in competing with foreign grown fiber still lay in mixing the short, or tangled, tow fibers with the long fiber flax, and in grading the flax properly. Joan Patterson of Oregon State University began experimenting in the late 1940s with linen woven in combination with other fabrics. Instead of being done with the long fiber flax she, too, used the tow which had formerly been burned as waste.

Her hand-loomed samples were applicable to power loom production, and samples from the Oregon Worsted Company were featured in magazines like House Beautiful, House and Garden, Modern Bride, Better Living, and Good Housekeeping after she previewed them in New York City in 1951. In 1952, National Automotive Fibers decided to concentrate its entire home rugs operation at the Salem plant in West Salem.

Between the linen mill, the flax textile mills, and the woolen mills, Salem in 1952 was rapidly becoming known as a textile center. Despite these hopeful signs, acreage harvested in 1952 was down, and plants throughout the Willamette Valley were closing. The following year, a drop in the price of flax fiber threatened operations at the penitentiary, which employed 250 convicts and, in 1954, they were the only plant still in operation in Salem. The availability of lower-priced foreign fiber and the labor-intensive production methods were key factors in the decline.

Just getting the flax from the field to the mill was a lengthy process. After the August harvest, loads of bundled flax straw were pitched off the farmer’s truck and stacked in a storage shed. The flax was later hauled out and each bundle untied, then put through a de-seeding machine, then retied and hauled back to storage until the following summer. Then it was hauled out again, pitched into a “retting” tank where bacterial action loosed the fibers from the woody parts of the plant. Then it was hauled into the field and stacked in wigwams to dry. Once it was dry a year after harvesting, it was hand-tied again and stored until winter, when the moisture content would be higher and it could be “scutched.” It did not matter in the 1950s that there were machines available to automate the process – no one could afford them. There was a brief period of hope in the late 1950s, but the new companies were not successful, and another period in Salem’s history came to an end.

Researched and written by Joan Marie “Toni” Meyering

Bibliography:

“Flax: A Growing Industry in Oregon” (brochure).

Meyering, Joan Marie “Toni”. Unpublished paper.

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment