Readers should feel free to use information from this article, however credit must be given to the Willamette Heritage Center and to the author.

By Charles Cheney

At the U.S. Capitol, a National Statuary Hall Collection has been erected to honor one hundred of the finest individuals in American history –two from each state. Due to its limited size, the assembly of revered Americans is devoid of numerous people who would easily rank among the hundred most influential Americans of all time. These ranks include Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, just to name a few. Considering these facts, it is telling of his significance, both to the State of Oregon and the United States, that Jason Lee is one of the two individuals representing Oregon in this great congregation. Who exactly was Jason Lee, and why is he so highly esteemed?

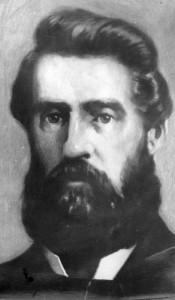

Jason Lee was born in 1803, in Stanstead, Quebec. The youngest of fifteen children (the oldest of whom was twenty-five years his senior), Lee grew up under the care of his older siblings after his father died in 1806. Biographer Cornelius Brosnan notes that “at the age of thirteen, Jason Lee was self-supporting…a farmer boy in a new country

That cause presented itself to him in his twenty-fourth year. At that time, Lee became what is often referred to as a “born again” Christian, through the work of Wesleyan revivalist Richard Pope.[2] Three years later, Lee entered the Wilbraham Academy in Massachusetts, where the minimally educated pioneer received a more formal education in preparation for Christian ministry.[3] Following his time at Wilbraham, Lee taught and preached in his hometown and the surrounding area until he applied in 1832 to work with the London Wesleyan Missionary Society. When a number of Northwest Indians visited St. Louis in 1831 asking for instruction from the “white man’s book” (the Bible), a call was issued for missionaries to head to Oregon. Lee answered this call and was appointed by the Methodist Episcopal Church as a minister to the Indians. After about a year’s worth of fundraising and other preparations, Lee and four co-laborers (Cyrus Shepard, Courtney Walker, Philip Edwards, and nephew Daniel Lee) joined the second expedition of Nathaniel Wyeth when it left Independence, Missouri, for Oregon in April 1834.

Following a journey of four and a half months, the Lee delegation arrived at Fort Vancouver on September 15, 1834. While originally sent to minister to the Flatheads, Lee found upon his arrival that “the real Flat Head Indians were few in number, and had no settled habitations.”[4] Additionally, Dr. John McLoughlin, the Hudson’s Bay Co. (HBC) chief factor at the fort, recommended to the missionaries that they select a mission location close to Vancouver so they could ensure protection in the event of an Indian attack.[5] Accordingly, Lee decided to settle in Kalapuya country, about sixty miles south of Fort Vancouver, along the Willamette River, northwest of what is today the town of Brooks. Here, in fall 1834, the missionaries built a barn and the original mission house, which was used for schooling, church services, and “domestic purposes.”[6]

During the next few years, crops were planted, cattle were purchased, children were educated, additional buildings were erected, and Indians, French trappers, and retired Hudson’s Bay Company employees were ministered to, all under the direction of Jason Lee. Serving as a pastor, as head of the mission, and as a builder and farmer; Lee personally experienced the strenuousness of too few workers doing too much work. During the first year, for example, Lee did more than his fair share of hard and time-consuming work on the mission property, making window coverings, preparing lumber for floorboards, doors, and tables, and “fencing and cultivating land.”[7] Realizing, then, that more manpower was needed to maintain the work of the mission, Lee asked his mission board to send additional workers. This request met the approval of the board, and a doctor, blacksmith, carpenter, and three single women were sent, leaving Boston in July 1836 and arriving at Fort Vancouver in May 1837.[8] One of those single women was Anna Maria Pittman, who, within three months was no longer Ms. Pittman, but Mrs. Lee.

With the settlement increasing in population and its future prospects being weighed, Reverend Lee left the Oregon Country in March 1838 for a two-year visit back in the United States. He held gatherings throughout the U.S. to collect funds for the mission. At the same time, he sparked interest in future settlement of Oregon through his descriptions of the land and through the presence and testimony of two Indian boys who had come with him on his journey.[9] Finally, he assisted the fledgling settlement by presenting to Congress two petitions – one from him and the other from the settlers already in Oregon – requesting that Oregon be granted territory status and be provided a governor.

The trip affected Lee and the Oregon settlement in three additional ways. First, Lee brought back with him “materials for the construction of grist and saw mills.”[10] These mills would help break the monopoly on trade held by the HBC,[11] and contribute toward the commercial development of the American settlement. In addition, Lee brought back with him a group of forty-five reinforcements who carried out the job duties of missionary, farmer, teacher, cabinet maker, blacksmith, and physician. These individuals rounded out the workforce at the mission, allowing its work to be carried out more efficiently and providing it the resources to be self-sustaining.[12] Third, and on a personal level, while back in the United States Lee received news of the death of his pregnant wife and their baby. Before returning to Oregon, he heard of, met, wooed, and married his second wife, Lucy Thompson.

More workers allowed more work to be done, but also provided more opportunities for interpersonal conflict. Distance made communication with relatives back home difficult, leading to isolation and loneliness. Harsh natural conditions led to several deadly accidents. Converts were few, and the missionaries were forced to spend most of their time in temporal instead of spiritual work. Sickness and death plagued both the missionaries and the natives; Lee lost both his wives in childbirth, and the Indian Manual Training School lost numerous students as many Indian children died of disease. Combined, these factors ultimately brought about the end of Lee’s work in Oregon.

Disheartened and disgruntled missionaries wrote home to the Mission Board complaining of Lee’s leadership. The Board began to wonder about him as well, coming to the belief that Lee had selected a bad location for the mission and had made several unwise selections of missionaries (By 1844, Lee was able to attest that eleven missionaries were either lukewarm about the ministry in Oregon or desired to abandon it altogether.)[13] Financial accusations were also leveled against Lee: cattle speculation, requesting too large a salary, and failing to fully report financial transactions and accounts. As a final blow, one of the other missionaries complained of the cost and sustainability of the mission – it had cost upward of $100,000 to that point.

Knowing that charges had been leveled against himself and that the mission board was unhappy with him, Lee sailed East during the winter of 1843-44 to report to them in person. During his journey there, Lee learned that the board had replaced him as superintendent of the mission. A few months later, during a nine day conference with his superiors, Lee deftly defended himself against the charges that had led to his dismissal. His cattle had been sold for only as much as they had been purchased. Regarding his salary, he had always refused to be paid more than ministers in the States. As for his leadership, the mission location had been approved by other mission members, and the selection of missionaries was done through the board itself. Finally, regarding the mission’s effectiveness and cost, Lee admitted that it had not resulted in large numbers of converted individuals, and that it had cost a significant amount of money. However, the mission had been instrumental in the conversion of a number of whites, had helped prevent bloodshed at the hands of both whites and natives, and had become somewhat self-supporting through productive endeavors such as the farm and the mills. Convinced of his sincerity and the truthfulness of his testimony, the Board cleared Lee of all charges.

Despite his acquittal, Lee could not regain his position in Oregon. Rev. George Gary – the new Superintendent – had left for Oregon well before Lee arrived in the East, and it was too late to recall him. Nonetheless, Lee continued his work for the fledgling settlement. He soon obtained a commission as “agent for the Oregon Institute”, and went to work raising funds for the school, hoping to return soon to Oregon.[14] Sadly, this was a short-lived appointment, and Lee never saw Oregon again. Suffering from a persistent cold, he slowly lost what to that point had been generally robust health and strength. During the winter of 1844-45, Lee continued to waste away until on March 12, he breathed his last in the presence of his family in Stanstead.

Quite simply, what sets Jason Lee apart as a leading figure of Oregon and American history is the determination and purpose with which he carried out his work in Oregon. Perhaps these were the characteristics Lee’s Wilbraham principal, Wilbur Fisk, had in mind when he wrote, “We are for having a mission established there [with the Flatheads] at once…all we want is the men…I know one young man, who, I think will go, of whom I can say, I know of none like him for the enterprise.”[15] In eleven years, Lee endured the following: over twenty thousand miles of travel; the loss of two wives, one baby, numerous fellow workers and many Indian neighbors; physical stress in the forms of extreme sickness, isolated and at times unaided hard labor, and rugged, sometimes dangerous environmental conditions; emotional stress in the forms of warring peoples (Indians and whites), excess responsibilities, and persecution from coworkers (one of whom, remarkably, was the man the virtuous Lee entrusted with the care of his orphaned daughter in 1845). Because he withstood these challenges, the mission held together, and thus laid the foundation for further American settlement and, ultimately, the state of Oregon. In addition, while engrossed in the same work as others, he found the time and energy to help form and to be a trustee on the board of the Oregon Institute (today’s Willamette University), to participate in (and chair one of) the meetings that established the Oregon Provisional Government, and to provide information for the Slacum Expedition’s report to Congress.

Who was Jason Lee that so much could be expected from him? He was no politician, but simply a pastor and missionary. He was not an explorer or pioneer by trade, but a humble and hard worker who wished to serve his God and fellow man. Nonetheless, Jason Lee was a significant – often leading – contributor in every effort that made Oregon an American territory and state. Though he was by no means the only person to die in the pursuit of American settlement in Oregon, Lee made a more direct and costly investment than others in forming Oregon. While brave men and women died on the Oregon Trail, in the quest for better lives for themselves, Lee died during a respite from his work, as a man who had given up a good life back east to exhaust his youth in order to improve the lives of others. And while other selfless missionaries died in that same effort, Lee’s humble and farsighted leadership, and his determined strength, make him unique among even them. These characteristics of self-sacrifice and exceptional leadership set him apart as worthy of the honor he has received.

[1] Cornelius Brosnan, Jason Lee: Prophet of the New Oregon, (New York: MacMillan Co., 1932), pg. 23.

[2] Ibid., 24.

[3] Ibid., 26.

[4] Charles Henry Carey, ed., “Methodist Annual Reports Relating to the Willamette Mission (1834-1848,”Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, 4(23), pg. 306

[5] George H. Himes, “Beginnings of Christianity in Oregon,” Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, 2(20), pg. 164.

[6] Carey, 310.

[7] Brosnan, 260.

[8] Ibid., 88-9.

[9] Ibid., 282.

[10] Frederick V. Holman, “A Brief History of the Oregon Provisional Government and What Caused Its Formation,” Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, 2(13), pg. 91.

[11] Brosnan, 222.

[12] Carey, 314.

[13] Brosnan, 259.

[14] Ibid., 271.

[15] Robert Moulton Gatke, Chronicles of Willamette: The Pioneer University of the West, (Portland, OR: Binford & Mort., 1943), pg. 7

Leave A Comment