by Richard van Pelt, WWI Correspondent

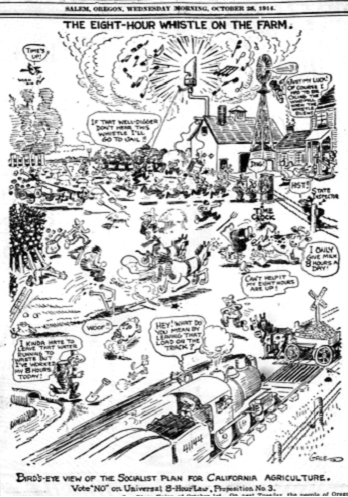

Locally the eight-hour day prompted the Oregon Statesman to publish the following political cartoon on its front page:

Editorially, the paper commented on the call by a Massachusetts Congressman for an inquiry into Uncle Sam’s military preparedness:

Every little while some salesman discovers that Uncle Sam is not prepared for war, and proceeds to sound a clarion call to arms. The latest alarmist is Congressman Gardner of Massachusetts. He introduced a resolution in the house . . . . calling for a military inquiry by a national security commission.

“A public investigation,” he says, “will open the eyes of Americans to a situation which is being concealed from them. The United States is totally unprepared for war, defensive or offensive, against a real power.

“The times is not yet come,” he added, “when the United States can afford to allow the martial spirit of her sons to be destroyed, and all the Carnegie millions in the world will not silence those of us who believe that bullets can be stopped with bombast nor powder vanquished by platitudes.

It’s eloquently and sincerely set forth, but it’s an old story.

“Unprepared” are we? Of course. When in all our history has this nation ever been prepared, except in the closing months of the civil war? It is our chronic predicament and the result of our fixed policy.

The “martial spirit” which Congressman Gardner wants preserved has never existed. We are not a military nation. We have fought when we had to, and fought well; but there has never been a time since the Cavaliers landed in Virginia and the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock that we went around looking for a scrap, or were eager for war if there was any other honorable way out of the trouble.

We refuse to bewail our present pacific plight. All the powers that might threaten us have their hands full already. Nobody is going to bother us until this war is over, at any rate; and then both victors and vanquished will be so weakened that they’ll be glad of a chance to recuperate. The terms of settlement may make future wars unlikely. At least, we can decide then, calmly and intelligently, whether it’s necessary to change our policy.

The paper went on to argue for a strong navy, “fit and ready as money and brains can make them.” “Any important wars,” the editorial states, “will presumably be defensive; and until rival powers consent to limit naval armament we had better keep a fleet to guard our shipping and our seaports, increasing its strength consistently from year to year.” “We want no big army; no great military class” and the editorial concludes noting that “The European imbroglio shows how excessive preparedness for war invites war. We are a peaceful nation, and proud of it.”

The editorial reflected a foreign policy theme that has been present since the founding of the country and resonates to this day.

“Germany To Win, Says Father There To His Son In Salem” read the headline in the October 28, 1914 Oregon Statesman. Gustav Voget, writes from Lübeck to his son in Salem, Fred Voget, a first generation immigrant. World War I was a war, with the exception of Belgium, with no clear aggressors and no clear victims. The war quickly became a total war, mobilizing the efforts of all, civilian and military alike. By 1915 attitudes had hardened as the initial optimism of a quick and decisive war faded. Support for the war effort in a war with massive mortality rates was of prime importance.[2] Race, religion, and nationalism became the ingredients of propaganda warfare. Newspapers, music, film, and literature were all used to keep citizens and subjects focused on the war. With newspapers reporting casualties in the tens of thousands with each major engagement, appealing to the irrational and the paranoid was necessary in order to deflect people from concluding that the war was futile and unnecessary. Both sides sought to gain the sympathy of neutral powers, of which the United States was the most critical. Each side demonized the other. Voget père describes the mood of the German people during the first months of the war and seeks to justify why Germany went to war. He writes following the Battle of Tannenberg, in which German forces dealt a crushing defeat to the Russian armies that had invaded Prussia in August. The battle, which the letter describes, resulted in the almost total destruction of the 2nd Russian army. Of the 150,000 men in the Second Army, only about 10,000 managed to escape. The letter begins with a justification for the necessity of the war, attributed to the perfidy of Great Britain: Lübeck, Germany, Sept. 17, 1914 My Dear Boy: Upon my return home I found your several letters written during the middle and latter part of last month, expressing your sympathy and anxiety for our welfare. I regret that you were compelled to read so many false reports sent abroad by our enemies during the first weeks of the war. However, things have developed much different from what they expected them to, and you no doubt will be rejoicing with us over the glorious victories of our troops. Antwerp will soon be in our hands, and after we get through laying mines from Ostend and Calais, whole England will be surrounded by a network of mines and then the day of reckoning with this perfidious nation will come. Everyone here in Germany says: “There will be no peace until England has been thoroughly whipped.” England demanded war intending to crush us, and war it shall have. Everything had been well and thoroughly planned by our enemy and if we had not outwitted them by our march through Belgium the French and English would have advanced through that country on our unfortified lines around Aix La Chapelle. We have numerous proofs that it was a concerted scheme between England, France and Belgium to attack us at the proper moment through the country whose neutrality we are accused of having disregarded. If we had permitted this to come to pass, not a word would have been said but since we have come through Belgium, England feigns the protector of the helpless, in horror proclaiming this breach of neutrality – one of the greatest crimes in the history of the world. But what if the Lion roars! Our people stand united against the overwhelming forces with full confidence of a successful ending of this war which was forced upon us in so cruel and treacherous a manner. You have no just idea of the enthusiasm which prevails throughout our Empire. Young and old, rich and poor alike are rushing to the standards until the government finds it impossible to accommodate all that want to serve. Everyone is full of hope and enthusiasm, determined that Germany must either win – or die. “England demanded war intending to crush us, and war it shall have. Everything had been well and thoroughly planned by our enemy and if we had not outwitted them by our march through Belgium the French and English would have advanced through that country on our unfortified lines around Aix La Chapelle.”[3] This was the version of events Germans would have read of in their daily newspapers. Print news, letters, and word of mouth were the only means by which news spread among the general population. Writing of how long the war would last and thinking about whether it could be avoided, he writes: A great conflict is ahead of us, and it will be many months yet before the war comes to an end, and many thousands of young lives will have to be sacrificed, but we will conquer in spite of the multitude of our enemies. You ask whether it would have been possible for Germany to have avoided this war. Basing my statement on facts which we now have on hand and which prompted our government in its actions from the beginning, I answer: No. We might have put this war off a little longer, thereby giving Russia a chance to first crush Austria, afterwards turning on us – together with France – which would have made it that much easier for them to overcome us, but we never could have avoided the war for the reason that Russia was determined to put a stop to Austria’s aggressiveness in the Balkan states. He writes of his nephews, the cousins of Fred Voget, and for the Voget family the war is immediate: From your cousins, we have heard nothing since they left for the front, with the exception of Herman Voget who was severely wounded near Metz in the upper left arm by a dum-dum bullet. It is a question whether he will be able to ever use his hand again. Both of his comrades on either side of him were killed outright on the spot. Your sisters’ husbands are still at home, anxiously waiting to be called to the front. Fred Voget has a brother, Julius[1] and their father is critical of the name given to his new grandson: As regards a name for Julius’ boy, I cannot help but say that I dislike the English sounding name he proposes and suggest that he call him after our glorious general, Hindenburg[2], who has distinguished himself so exceedingly by his courage and skills in the battles against the Russians. Gustav is referring at this point in his letter to the battle of Tannenberg, a crucial battle in East Prussia: When has it occurred before in history that 92,000 soldiers, unwounded, were made prisoners in an open field battle? To judge from your letters, you seem to be under the impression that we are not getting the assistance from Austria which we expected. This is a very erroneous idea and no doubt must be laid to the lies which our enemies so cruelly spread everywhere. They seem to be past-masters in the art of “manufacturing” war reports unfavorable to the Germans and Austrians. The facts are that the Austrian soldiers have done splendidly. They have captured more than 100,000 Russians with about 300 canons, and they will soon succeed in driving the Russians entirely out of Galicia. The Serbians also have received more than one good sound thrashing. No you need not worry. Our cause is faring splendidly, and our hopes for a complete victory and a thorough defeat of our enemies are quite strong. How plentiful our supply of soldiers and recruits is, you may know from the fact that this year’s roll call, comprising all serviceable men in Germany of the age of 19 years, have not yet entered the ranks, but they are waiting for their regular time which will as usual, in October. None of these men were permitted to report as volunteers. All the volunteers have come from men who had not yet attained the age of 19 years or from those, who for various reasons, were not compelled to enter the army. There is still a tremendous rush to the colors, and it is impossible to accommodate all those that want to serve. Even from America, thousands are willing to come if it were only possible to get them here. He writes of the feelings they have for the troops at the front. He describes the love they have for their Emperor, Wilhelm and describes the war as an instance of overreach by Great Britain. World War I took nearly everyone by surprise. International tensions there were and the balance of power in Europe was tenuous at best, as was apparent once the scope of the war was understood. Public opinion in all of the belligerent countries saw their participation as a defensive reaction to the decisions of the other side. This is not surprising given how the war expanded almost in the manner of a chain reaction. Austria felt justified in seeking redress from Serbia and when she mobilized, treaty obligations led to mobilizations across Europe. Each belligerent could argue that they were reacting in support of their allies. This was not like World War II, where, across Europe, the general public sensed that war could occur at any time. Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 clearly identified it as the aggressor; that could not be said with respect to the outbreak of war in 1914. After many days of beautiful sunshine, storm and rain have set in, and we are thinking with much sympathy of the poor soldiers on the battlefields, be they Germans or Austrians. The latter are fully as good as our own troops, and are worthy of our admiration. Only this afternoon I noticed an extra edition reporting a great victory of the Austrian forces at Lemberg. Yes, our enemies did not think that our peace-loving emperor would really draw his sword for Austria. When I was at London in 1911, how often did I hear the words: “The Germans fear England. They always ’draw back’ as soon as England threatens!”. And now they claim that our emperor should have caused this war. No, never. For forty-three long years he has maintained peace in the Empire. Many people have criticized him and found fault with many of his acts and policies, but their eyes are opened now, and whole Germany realizes that if it hadn’t been for the wise foresight of the Kaiser, and the untiring energy with which he maintained a powerful army and navy that an independent German Empire would have ceased to exist. He stands there today without a peer. He is almost worshipped by his subjects, and has the support of “one and all,” regardless of creed, party, or politics. The father presents the German position as being a potential victim of a Russia that seeks to dismantle the unified Germany that came into existence during the last half of the nineteenth century: It is no longer a secret that it was Russia’s intention to first crush Austria, afterwards turning on us. It has been proven again and again that it was a well laid plot, our enemies, even having drawn up maps already upon which they “graciously” permitted the German Empire to retain the size of one of our small principalities. France would never have declared war against us if it had not been assured of England’s assistance. What a comforting thought it must be for our emperor when he rides over the battlefield and sees the devastation, the many dead and wounded, to be able to look up to heaven and say: “Thou Oh Lord knowest that it was not I who wanted and caused this war. Thou knowest that it was forced upon me, and the day will come when Thou will make known my innocence before the whole world.” It seems that everybody has turned against us, for some reason or other, but mainly on account of the contemptible lies which have been scattered broadcast by our enemies, and which we are unable to refute at the present for the reason that our cable communications with the outside world have been severed; but in the end the right will conquer. What the public was told regarding the reasons for war differs from what the German Chancellor, Von Bethmann-Hollweg said to the German Reichstag on August 4th, 1914, justifying the invasion of Belgium: “We are now in a state of necessity, and necessity knows no law. Our troops have occupied Luxemburg and perhaps are already on Belgian soil. Gentlemen, that is contrary to the dictates of international law. It is true that the French Government has declared at Brussels that France is willing to respect the neutrality of Belgium, so long as her opponent respects it. We knew, however, that France stood ready for invasion. France could wait, but we could not wait. A French movement upon our flank upon the lower Rhine might have been disastrous. So we were compelled to override the just protest of the Luxemburg and Belgian Governments. The wrong—I speak openly—that we are committing we will endeavor to make good as soon as our military goal has been reached. Anybody who is threatened as we are threatened, and is fighting for his highest possessions, can only have one thought—how he is to hack his way through.”[3] The headlines in the Daily Capital Journal for August fourth reflect the growing scope of the war. This is what we would have read: Kaiser Declares War on Belgium, Belgians Ask Help KaiserLays Blame For War on Russia Points to His Acts Two Million Men Now Face to Face on Battlefield England Liable to Declare War at Minute’s Notice The German justification, as reported in the paper for that day states that “Belgium, it was declared, had forced the Germans to resort to force by refusing to facilitate the passage of German troops through its territory on their way to the French frontier.” Gustav Voget assures his son that life goes on as usual, despite mobilization and troop movements: Do not worry about us. We are getting along nicely and hardly realize that a war is being waged on the outside. Foodstuffs have not risen in price, and if it were not for the wounded which you can see in the larger towns, and some of the business houses being closed down, you would hardly know that on the outside of Germany a war is raging. In those cities where troops are stationed, the same drilling is going on as usual. The same battalions and regiments, clad in the familiar blue uniforms, are marching through the streets, going through their regular maneuvers on the drill grounds, etc., and when at times in the evening a regiment exchanges the blue for the gray uniform in order to leave for the front, the next morning the same number of men are taken on again, and the same routine of drilling continues. So, for instance, in the little town of Ratzburg where only one battalion of sharp-shooters is stationed, 4500 mean have been sent out already and 1500 men are drilling now, which intend to leave for the front in a few days in order to make room for other volunteers which are now waiting to take their places. Only recently I saw a proclamation in the paper stating that the ninth battalion of sharp-shooters and the 162d infantry regiment (in which you have seen service) were unable to take on any more recruits, at the present, as the demand had been fully covered. Assuring his son that Germany, contrary to published rumors in the United States, is far from being on the verge of defeat: Therefore, when some of the ill-informed people in the United States tell you that Germany is about “all in,” you may laugh at them and tell them that they are sadly mistaken, and that their ignorance is almost unbearable. They had better look out that the Japs do not get too fresh and commence to make them trouble before they know it. Yea, it is a crime that cries to heave, and causes a man’s blood to boil to think that England should fetch those heathens out of Africa and India to fight against a Christian nation. What will the heathens think of such “Christians!” Never before has a nation denied its Christianity in such a manner as England is doing right now! I must break off – for whenever my thoughts commence to dwell upon this my feelings become too strong to be expressed in words, and it is so with every man, woman and child in Germany. England alone is to blame for this awful slaughter and suffering, for it was the main instigator of all this trouble. He then relates news of family members who are on active duty: It may be interesting for you to learn that your cousin, Roper, who is a lieutenant in the reserves, has charge of an ammunition transport on the Russian line. It is his duty to bring up fresh ammunition to the big guns whenever they need it. Bert (another cousin) was married on the 11th day of September, and intends to leave for the front in the near future. He holds a lieutenantship in the reserves. Many officers have been killed, and it is good that we have such a large supply to draw from, and everyone has volunteered his services, even old General Haeseler, who is already 79 years of age and whom the emperor therefore did not care to intrust with the command of an army corp, has gone to the front as volunteer and “is attacking the enemy wherever he finds him.” Gustav then relates the state of German strength on the eastern front in East Prussia as well as in France: We have seven main armies in France and only one, the eighth, against Russia. It is stated that every army is composed of five army corps which would give each army about 250,000 men. Both in the east and west we are greatly outnumbered by our enemies, especially in Russia where there are two or three army corps to our one. Amongst those fighting against us are the Russian Guards, the elite troops of the Russian empire. They were sent home, however, with bloody heads by our Landwehr, but the Austrians have to bear the brunt of the Russian advance. The parents of a soldier who serves in a field hospital and whose duty it is to haul the wounded from the battlefield in a wagon, tell me that after the battle of Allenstein, the dead Russians actually lay piled up on the battlefield as so many shocks of grain. The battle must have cost the Russian general, Tannenberg (the writer is confusing the name for the battle with the name of the Russian commander, Alexander Samsonov) at least 140,000 men, 90,000 of whom were made prisoners. Hindenburg, the German general who won this victory has been out of actual service already for three years, and now is proving himself one of the most efficient generals we have. May it be his privilege to leave his “calling card” at St. Petersburg soon. Yes it borders on the miraculous to think of the many grand victories that have already been won. About 300,000 prisoners, many large guns and standards without number are in our hands. It was a beautiful sight, the papers report, when a regiment of African (sic, possibly meant Cossack) sharp-shooters made a charge on one of our infantry regiments. They were eight hundred in number, mounted on swift and beautiful horses, in their gorgeous uniforms. The colonel waited until they were within a distance of 500 meters when he calmly gave the command: “Fire,” and then again, “Fire,” and in a few moments of the whole splendid troop there were only 27 left to tell the tale. The Russians soon fall on their knees and beg for mercy when they get into “close quarters.” Defining your enemies as dishonorable, treacherous, and immoral is a theme common among the belligerents. The writer is no exception: The manner in which our enemies carry on their warfare is simply fearful. Hundreds of our men have been shot from ambush, out of houses, schools and churches, by the treacherous English and Belgians and a trail of devastation and blood was left by the Russians as they retreated out of our east Prussian provinces upon the arrival of our troops. Even women have taken part in the fighting. In Belgium the colonel of the ninth battalion of sharp-shooters was shot down by a woman. Ten year old girls are known to have put out the eyes of German wounded as they lay on the battlefield. In many instances their ears and noses were chopped off. Only yesterday a young Red Cross nurse arrived at the local hospital with both her hands chopped off while attending to her duties in France. This then is the reward for her services of love and mercy. One of our acquaintances wrote us the other day that when friend of hers went to a hospital at Crefield to visit her husband who had lost a leg in the battle, that she found him with his head tied up also. Upon inquiring into the reason for this she was told that both of his ears were cut off while he was lying on the battlefield. In spite of the reports of our enemies to the contrary, our soldiers are behaving like gentlemen. Again and again wounded men bring back a report of the great unwillingness with which our troops execute the Franctireurs that have been caught. There is no alternative for this, however, for if you pardon them they will shoot down their benefactors at the first opportunity that present itself. In many instances the English have displayed white flags in order to draw on our unsuspecting troops only to open fire on them at the proper time and mow them down in large numbers. The Indians, I am sure, have displayed more humanity and leniency than is being manifested by our enemies in this war. But just the same we move on victorious. Our troops were ready, are ready, and will be ready to win or die. On of the emperor’s sons has been wounded already. It is said of another one that he took the drum of a dead drummer and beat the march for a general assault himself. So you see the German Empire is “one” from the emperor on his throne to the peasant in his humble cottage. Yea, let us of good cheer: the God of our Forefathers is on our side and with his help we will conquer. Lovingly, your father, G. H.Voget Voget’s refers to Franctireurs. Franctireurs were irregular forces practicing what we would today call asymmetric warfare. During August and September in France and in Belgium, the German army engaged in reprisals against civilians in both countries, though atrocities in Belgium were more widely advertised. From the German perspective, the real travesty was civilian resistance in and of itself. Subsequent research confirms that the Germans did commit international war crimes. After the war, the United States resisted efforts to institute and international war crimes court and the postwar Weimar government in Germany refused to accept any responsibility for war crimes. What follows are posters from the period using Belgium as a spur to enlistment: [1] Julius appears in the 1910 census as living in Ward 4 in Salem (Year: 1910; Census Place: Salem Ward 4, Marion, Oregon; Roll: T624_1284; Page: 1B; Enumeration District: 0224; FHL microfilm: 1375297) In 1920, the family had moved to Hillsboro [2] He would have wanted his grandson named Paul, after the general. Julius Voget named his son Herman according to the census records. [3] The Project Gutenberg eBook of The New York Times Current History of the European War, Vol. 1, January 9, 1915, by Various, p. 8 [1] According to the 1910 census, Fred Voget was born about 1881 in Germany and lived in Ward 4 in Salem [2] Rumania, for example, mobilized 750,000 troops. 45% died in combat, 16% were wounded, and 10.7% were missing or captured. [3] The writer describes the von Schlieffen plan. German strategic thinking was based upon the theory that Germany would be at war with France and Russia simultaneously, that France was weak, but that Russia would take longer to mobilize. As events unfolded, it was Russia that rapidly mobilized, and Germany was at war in the east, but not in the west with France. Germany had to divert forces to the east when their plan called for a swift movement through Belgium and into France. Belgium refused to grant the Germans transit through their country, and Belgium’s stiff and unexpected resistance permitted the French to stabilize the front. Germany’s invasion of Belgium triggered Britain entering the war in order to meet her obligation to defend Belgian neutrality.

Leave A Comment