The Willamette Heritage Center’s Research Library and Archive recently received an inquiry asking about the naming of Salem’s Electric Avenue. I’m not going to lie. I dread questions about the history of street names. There are rarely any definitive sources. I can look back at maps and plats and make some assumptions based on proximity to landmarks, but rarely is the rationale captured in something as simple and concrete as a diary entry or interview. It is a lot of guess work. I don’t like guess work.

However, every time I pass by Electric Avenue I immediately (and sometimes loudly) start singing the early 1980s hit song of the same name by British singer/songwriter Eddy Grant. I, too, often wonder about the name’s history. Unlike the Brixton-based street in London referred to in the song,[1] there was no evidence that Electric Avenue was anywhere near Salem’s first electrification projects.[2] So how did the street get its name?

In Salem, for most of its history, streets got named by the person or entity filing a plat with the county. This practice could be chaotic, sometimes leading to streets running along the same lines, but broken up by an obstacle, having multiple names assigned to it. Retroactive renaming and renumbering have happened quite a bit in an effort to add a little more order and logic for things like mail delivery and general wayfinding. During debate around a proposed, but never adopted street naming ordinance in 1904 an editorial comment in the Oregon Statesman opined:

The mayor has had the matter of renumbering of the streets in hand for some time, and yesterday completed the proposed ordinance and the Statesman takes pleasure in offering the text thereof to its readers. This is in line with modern ideas in street numbering and in line with the suggestions of the government for the easier delivery of mail. The Statesman tried hard to get the same system now proposed accepted by the city council when the first numbering ordinance was adopted nearly twenty years ago, but it was impossible, some people who had the matter in charge at the time declaring that there was no use in having more numbers than there were buildings to the block. This proposed measure is greatly in the way of advancement.[3]

The mayor’s proposal was to basically rename all the north-south streets in Salem as numbers starting at Water Street next to the Willamette River and increasing as you went east. It would have also renamed State Street as “Base Street” and then reordered all the east-west streets as North or South A, B, C. D, etc. Streets, moving away from Base Street.[4] Clearly, the proposal did not pass, given the wide variety of non-numerical and alpha street names in today’s downtown. It does provide a little bit of context to the difficulties of the hodgepodge naming system that had prevailed.

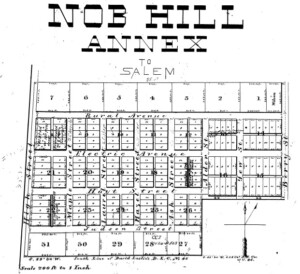

As far as I could find, Electric Avenue first appears in the July 7, 1891 plat of the Nob Hill Annex.[5] If you are ever curious, most of the plat maps for the City of Salem are accessible for free and online through the Survey Graphic’s Index maintained by Marion County: https://gis.co.marion.or.us/surveygraphicindex/. It is an amazing resource.[6] In 1891, Electric Avenue extended from High Street to Berry Streets crossing Maple, Laurel, Hazel, Ash, Alder and Yew Streets. All the tree streets, but Yew, would later be renamed (Church, Cottage, Winter, Summer, etc.) to match their counterparts further north.[7] The Nob Hill Annex plat was filed by J.H. Albert and C. Morelock and included thirty-one blocks and 307 lots.[8]

Perhaps the best clue to the naming history of Electric Avenue comes from an article written by Lewis Judson and published in 1971 talking about the history of Salem Street names. In his description Judson writes: “Some of the names, such as Trade and Market, given to streets seem to reflect the hopes of the platters…Electric Avenue was a real estate promoter’s dream in which was envisioned an electric car line on the east-west street, connecting the line on Commercial Street with the one on Twelfth Street and thus forming a loop road.”[9]

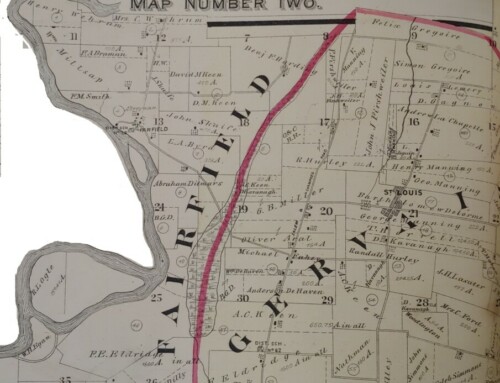

It seems likely this reference to a real estate promoter meant John H. Albert. Albert, a banker by trade, had his fingers in a lot of pies including real estate development, manufacturing start-ups like the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill[10], and Salem’s early streetcars. In 1888 he helped incorporate the Salem Street Railway Company, which would start Salem’s first, horse-powered street-car lines.[11] By the time Albert was platting the Nob Hill Annex, street car companies had extended tracks south on 12th Street to about Lewis Street and south on Commercial Street to the Pioneer Cemetery.[12] The Nob Hill Annex was located between the two.

Just a few days after the plat for the Nob Hill Annex was filed, the newspaper reported J.H. Albert was applying to the county court for a franchise for what they described as: “practically an extension of the Salem Street Railway.”[13] Albert’s plan was to extend the Salem Street Railway tracks on 12th street a few more blocks south, and then to run westward on Electric Avenue to the I.O.O. F (now Pioneer) Cemetery. His hope was to electrify the new line. Up until this point the Salem Street Railway system on 12th street had been pulled by horses.[14]

For those familiar with the street layout of the area today, this may not seem plausible, but through the platting of the Nob Hill Addition in 1892[15], the original Electric Avenue did indeed extended to a juncture with South Commercial Street. Subsequent developments in 1910 obscured the original street plan.[16] The newspaper made note of the advantages such a line would have brought to Albert as the platter of the Nob Hill Annex: “The projectors have platted the Nob Hill annex, which property is penetrated by the proposed extension so as to make it valuable residence property.”[17]

An electric streetcar line up Electric Avenue was the plan, but as with so many plans it wasn’t meant to be. Albert secured the franchise, with the provision that the work on the line started within six months of the grant and that it was in operation within a year.[18] A year had not passed, however, before a new franchise was sought, this time by Albert and a consortium of other developers. The route had changed a bit, too. Instead of a straight shot up Electric Avenue, the new route would run an inexplicable curving course starting at Hoyt Street, making a northward turn at Winter Street to Electric, at Electric turn east to Berry, north at 11th to Cross and then run east from Cross Street to 13th Street. Little rationale was given for the new route, but it is interesting to note that many of the petitioners listed owned or had platted property that was now adjacent to or crossed by the new route.[19] This new franchise had an even shorter expiration date. It would be nullified if work didn’t start within 6 months of the date. It looks like it didn’t make the mark, as no evidence could be found for the connection ever actually being built.[20]

All that remains of Albert’s big idea is one short street with a catchy name.

This article was researched and written by Kylie Pine. It appeared in the Statesman Journal newspaper in February 2022. It is reproduced here with full citations for reference purposes.

John H. Albert

John Henry Albert was born in 1839 in Wheeling, Ohio County, West Virginia.[1] He studied the law, worked as a merchant, taught school, and eventually went into banking. He started the Capital National Bank in Salem and was involved in a variety of community building activities.[2]

Albert was married three times to Theodosia Burr Berry, Mary Elizbeth Holman and Elizbeth McNary. He had five children including:

- Joseph Holman Albert (1868-1939)[3] worked as a cashier in his father’s bank.

- Myra Albert Wiggins (1869-1956) who became an accomplished painter and photographer, being part of the Photo Secessionist movement with the likes of Alfred Stieglitz.

- Blanche Albert Rogers (1872-1954). Blanche’s huband George F. Rogers was mayor of Salem from 1907-1910.[4]

- Harry Ebin Albert (1874-1946) worked as a federal bank inspector[5]

- Alberta Albert (1885-1885)[6]

Citations

Electric Avenue

[1] Urban, Mike. “The Rise and Fall of Electric Avenue.” Brixton Buzz. 22 Aug 2013. https://www.brixtonbuzz.com/2013/08/the-rise-and-fall-of-electric-avenue-brixton/ — “Famed and named for being one of the first streets in Britain to be lit by electricity, this archive view from 1910 shows off the elegant glazed iron Victorian canopies that once graced Electric Avenue.”

Simpson, Dave. “How We Made Eddy Grant’s Electric Avenue.” The Guardian 3 Sept 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/sep/03/how-we-made-eddy-grant-electric-avenue — from interview with Grant: “On the way home one night from working in the Black Theatre of Brixton I saw Electric Avenue on a street sign, and thought: “What a fantastic song title.”

[2] The first tests of electric lights at the Oregon State Capitol grounds was conducted in 1886. https://www.willametteheritage.org/electrifying-salem/ . Note the 1890 article talking about a wedding beneath an electric street light on Court and Church Streets in 1890, a full year before the street was even platted. https://www.willametteheritage.org/love-under-electric-lights/#_ftn1

[3] “Renumber city.” Oregon Statesman 07 Aug 1904 pg. 3

[4] “Renumber city.” Oregon Statesman 07 Aug 1904 pg. 3

[5] Nob Hill Annex July 7, 1891https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4076006

[6] Marion County Survey Graphic Index link: https://gis.co.marion.or.us/surveygraphicindex/. Want to learn how to use the site? Check out our Couch Historian Tutorial here: https://www.willametteheritage.org/research/couch-historian-webisodes/. Episode 6.

[7] See notations on plat map (hand drawn) for street renaming. Nob Hill Annex July 7, 1891 https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4076006

[8] Nob Hill Annex July 7, 1891 Plat. See text. https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4076006

And “Addition.” Capital Journal 08 Jul 1891 pg. 3

[9] Judson, Lewis. “Reflections on the Jason Lee Mission and the Opening of Civilization in the Oregon Country.” 1971. WHC Collections 81.7.18).

[10] Lomax, Alfred L. Later Woolen Mills in Oregon. Binford & Mort, 1974 pg. 19. Lists J.H. Albert as the Committee of the Fundraising committee to bring a Woolen Mill to Salem and served in various fact finding capacities.

[11] Maxwell, Ben. “Salem’s First Streetcar Line.” Marion County History Vol 6, 1960 pg. 21.

[12] See 1892 Union Abstract Map. Available here: https://www.willametteheritage.org/1892-map-of-salem/. Also Maxwell, Bn. “Salem’s First Streetcar Line” Marion County History Vol 6, 1960 pg. 23 describes tracks extending to Odd fellows cemetery in 1890 pg. 23. Could not find matching newspaper article when I looked.

[13] “Heading ‘em off.” Capital Journal 11 Jul 1891 pg. 3

[14] “Heading ‘em off.” Capital Journal 11 Jul 1891 pg. 3. The new franchise starts from the present terminus of the horse car line of 12th street, extends three blocks south, thence west to Commercial Street at the IOOF Cemetery. ..He is in correspondence with eastern parties and says he will secure the electrifying of the old street railway and the new extension…so Salem is sure of another electric line.”

See Also: “More Street Railway Lines.” Oregon Statesman 11 Jul 1891 pg. 4. J.H. Albert and associates petitioned for the right of way to locate a street railway on the road known as 12th street and Electric Avenue to the Rural cemetery…. The petition asks to be permitted to run cars propelled by steam, electricity, or horses.

[15] Nob Hill Subdivision 3 July 1892

https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4076029&cr=1

[16] See Amended Plan of Blocks 27, 28, 30, 31, & 32 of Nob Hill Addition to Salem Oregon, dated 1910 for how street plan was changed. https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4076172&cr=1

[17] “Heading ‘em off.” Capital Journal 11 Jul 1891 pg. 3

[18] The Franchise was Granted. Oregon Statesman 12 Jul 1891 pg. 4

[19] Gray Brothers and W.E. Burke show up in this plat of the Pleasant Home Addition which would be better served by the streetcar passing through it. See 1890 Plat Pleasant Home Addition: https://secure.co.marion.or.us/weblink/DocView.aspx?id=4075955&cr=1

[20] No newspaper articles past the franchise date related to it. Doesn’t appear on the 1892 map of Salem and I can’t find it in Ed Austin and Tom Dill’s map of Salem Street Car Lines accessible via Oregon Encyclopedia Article: https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/salem_streetcar_system/

Biography of John H. Albert

[1] A preponderance of sources claim birth in Virginia/West Virginia, despite an obituary in the Oregon Journal (“John H. Albert, Bank Founder, Dies at Salem at age of 80” Oregon Journal 30 Dec 1920)

See his 1900 Passport Application (DOB 8 Feb 1839 West Virginia) accessible via Ancestry.com–1900 Passport Application; Oregon Statesman Obituary (“Long, Active Life of John H. Albert is Closed by Death.” Oregon Statesman 31 Dec 1920 pg 1); Grave Stone gives birthdate as 1839: John Henry Albert (1839-1920) – Find a Grave Memorial; 1870 US Federal Census; 1880 US Federal Census; 1900 Federal Census; 1910 US Federal Census; 1920 US Federal Census;

[2] “John H. Albert, Bank Founder, Dies at Salem at age of 80” Oregon Journal 30 Dec 1920; “Long, Active Life of John H. Albert is Closed by Death.” Oregon Statesman 31 Dec 1920 pg 1

[3] Oregon State Death Records. Marion County. State Register No. 4, 1939. Accessible via Ancestry.com; Find a Grave Memorial: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/57883703/joseph-holman-albert

[4] “Services for Mrs. Rodgers set for Saturday.” Oregon Statesman 17 Jun 1954 pg 15; Findagrave: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49529496/blanche-rodgers

[5] Oregon Death Records. Multnomah County. State File No. 1528 Local Registrar 1530. Accessible via ancestry.com

[6] FindaGrave: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23983388/alberta-albert

Leave A Comment