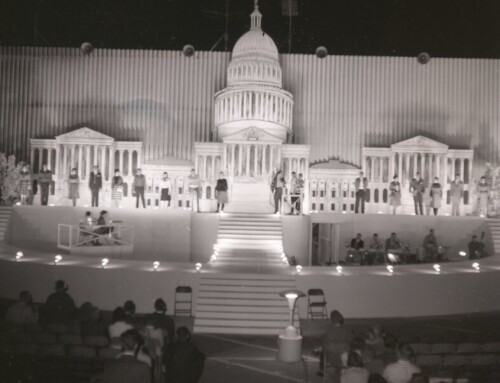

Century-old cemetery at Salem became center of civic attention when woolly flocks were turned loose this spring to graze among the ancient tombstones.

reprinted from The Sunday Oregonian Magazine August 23, 1953

Various Salem residents who have wandered by the town’s 100-year-old Pioneer cemetery on recent warm summer nights have been scared out of a year’s growth by ghostly bleatings from among the moss-covered tombstones.

According to the Salem Statesman, late hour pedestrians “…get quite a jar when they see dim white forms moving silently among the graves. One woman passerby was nearly jolted out of her powder base when a woolly white figure leaped out from behind a tomb-marker near the fence the other night…”

All this serves to point up a problem that has been troubling the citizens of Salem and Marion county, legal custodians of the century-old burying ground on S. Commercial Street which holds a high percentage of Oregon’s most illustrious and honored dead.

Honored dead, that is, in the history books, because over the long years the spot where they are buried became such a tangle of weeds, brambles, brush and crumbling tombstones that passersby have called it “Hell’s half acre.”

The last legislature gave the people of Salem and Marion County the duty of restoring and taking proper care of the graves in the old cemetery known as the Odd Fellows. But lacking funds, the people of the capital area late this spring launched a unique experiment in cemetery renovation. They turned the ancient plot into a sheep pasture.

As soon as the legislature adjourned the Marion county court encircled the tombstones within a woven fence and trucked in 300 sheep, giving to those quadrupeds the task of eating away the evidences of decades of neglect.

The sheep have browsed happily away in the graveyard during the spring and summer months, and truckloads of cans and other non-edible rubbish that they uncovered have been trucked away, but the beautification project still is a long way from finished.

The introduction of sheep to the cemetery naturally stirred a controversy. “Desecration” is the word some natives let fly who prefer weeds to sheep.

However, many families owning plots in the old cemetery have been willing to overlook the unorthodox method of cleaning the grounds up, believing that the end result will be worth it.

As the sheep, now reduced in number to 25, have cleared every weed and brush, it has become apparent that considerable labor will be needed to finish up the renovation.

Among the protesting letters “To the Editor” came one from the grandmaster of the Odd Fellows in Oregon asking that the lodge name be dropped. The Oregon Statesman, two years older than the cemetery and whose first great editor, Asahel Bush, is buried there, suggested the substitute name “Pioneer” cemetery.

Salem townsfolk have worried a long time about the Odd Fellows cemetery. It’s not where they can forget about it. On a hill overlooking the capitol, it is flanked on one side by 99E, on another by a ranch house development, and on a third by the homes of the extra-well heeled.

Cemetery tombstones shouted their shameful neglect to an ever-present public. There in the weeds but easy to read was “A Justice of the Supreme Court of Oregon” – there “A Member of the Oregon Constitutional Convention” – over here “A Soldier Who Served Under General Andrew Jackson” – yonder a stone “To Honor One of Those Patriots who on May 2, 1843, Founded the Provisional Government at Champoeg, Oregon.”

In 1946 Salem’s Chemeketa lodge No. 1, IOOF, often blamed unjustly for the latter day condition of the cemetery bearing its name ran “an open letter to the public concerning the Odd Fellows cemetery” in both Salem papers.

The letter told how the cemetery came to be called Odd Fellows. One of the first thoughts of the pioneer settlers, heartsick over leaving their dead in ramshackle graves on the prairie, was for a cemetery in the new land.

The infant Odd Fellows lodge as a community project in 1853 developed a five-acre tract about 1 ½ miles from the village of Salem and offered graves for sale to the settlers at $1.25 a grave. There was not any promise of perpetual care. Such things were unheard of in those days. Each family cared for its own graves.

The settlers set aside one day each year for such care, on which they visited the cemetery, men, women, and children, with horses, wagons and picnic lunches. They cleaned their graves, collected the debris and hauled it away.

The Odd Fellows cemetery grew as did Salem until it encompassed 30 acres. But with the passage of years, relatives drifted away and the remaining descendants, increased to the fifth and sixth generation, lost interest in the graves of their forbears. Thus, an humanitarian venture of the Salem Odd Fellows came back to haunt them.

When I was a kid there was a family story that my grandfather’s sheep had been used at the cemetery to clean it up. I wonder if these were his sheep.