This year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the Prohibition Era in our country. While we often romanticize this epoch with images of flapper dresses, speakeasies and gangsters, the road to and from prohibition had much more complex political, economic, and social effects than that – especially in our city.

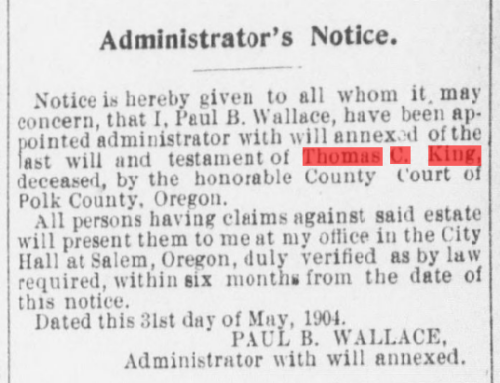

Believed to be the Standard Liquor Co. Salem on Commercial Street in Salem. WHC Collections 2007.001.1133

National Prohibition Legislation Complicated

The 18th Amendment to the United State Constitution, prohibiting the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” was finally ratified by the states on January 16, 1919, over a year after it passed congress.[1] But the ratification of the constitutional amendment wasn’t the end of the political saga. The amendment itself was worded to take effect one year after the ratification, and it delegated the enforcement of the law to Congress and the states.[2] Enter the National Prohibition Act (or more specifically “An Act to prohibit intoxicating beverages, and to regulate the manufacture, production, use and sale of high-proof spirits for other than beverage purposes, and to ensure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye and other lawful industries”). With a title like that it is no wonder it soon got nicknamed the Volstead Act after Republican Representative and bill sponsor Andrew Volstead of Minnesota.[3] This bill defined what an “intoxicating liquor” was and provided actual consequences to those dealing in it.[4]

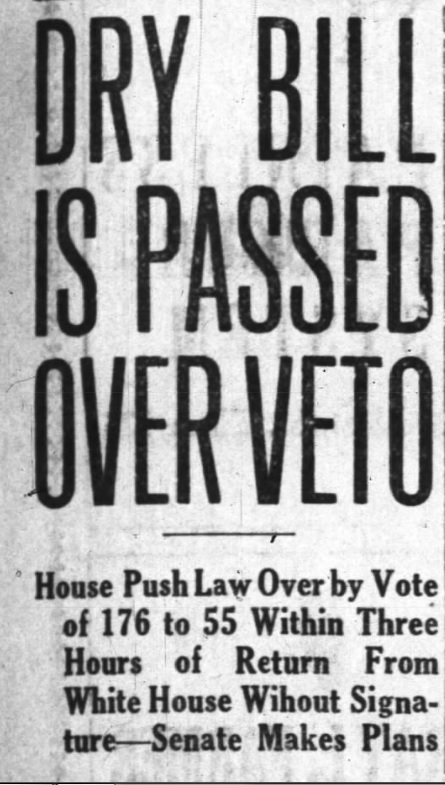

While the Volstead Act was approved by both houses of Congress by October of 1919, it was vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson. With an efficiency rarely seen in that august body, the veto was overturned in the House of Representatives within three hours of the president’s veto.[5] This led to an article in Salem’s Oregon Statesman predicting that “the refusal of the house to accept the president’s veto meant that the sale of liquor would not be permitted again in the life of this and many other generations.”[6]

As dramatic and final as this prediction was, it wasn’t the case. The provisions of the Volstead act wouldn’t go into effect until January 1920,[7] and we all know that the 18th Amendment would be repealed 13 years later thanks to the 21st Amendment.[8] Add to that the fact that the U.S. was already under a war-time ban on the sale of alcohol that had gone into effect in July of 1919. The rushes on saloons and stores had already happened by this point.[9]

Salem Already Dry

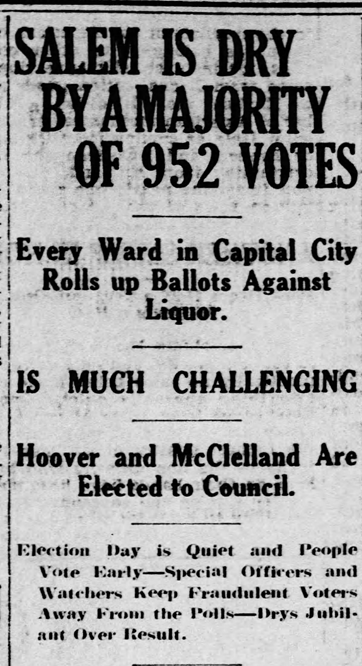

The change was no earth-shattering occurrence for Salemites of 1919 either. Salem voters had passed a city-wide ordinance for prohibition of alcohol way back in December of 1913.* It got held up in the courts but was pretty much in full force by 1914.[10] Oregon also anticipated the national trend, passing statewide prohibition legislation in 1915.[11]

Prohibition had adverse effects on certain elements of our local economy. While the city’s four-million-dollar-a-year hop industry continued to flourish[12], that was not the case for Salem’s brewery and 15 saloons.[13] After Salem’s ban was initiated, authorities allowed the Salem Brewery Association to continue brewing beer, but not “sell barter or trade its products in Salem.”[14] This reprieve didn’t last long, however, and the Salem Brewery Association ceased brewing beer in 1915.[15] The company and its facilities were reorganized in some pretty creative ways. To learn more about some of the alternative products they marketed check out this post.

Salem’s saloons and retailers were not so lucky, although the paper hints at some entrepreneurial spirit arising when faced with adversity. As one Capital Journal article reported “Most of the buildings formerly occupied by saloons were already advertised for rent or remodeled for some other class of business. Billiard tables, soft drinks and other mild refreshments are being supplied to the old patrons in some, and, with the exception of two or three, all of the stocks of liquor have been shipped away from the city.”[16]

Continuing Debate

Prohibition continued to be a hot topic, long after the local and national bans, especially as it became a campaign issue in the 1928 presidential election.[17] In perhaps my favorite piece of “on the street reporting” ever, journalists with the Oregon Statesmen collected opinions from around Salem on the issue. As they prefaced “Personal views are widely divergent on this moot subject. Almost everybody has a definite idea as to the situation. Salem folks are prone to do their own thinking.” I can’t reproduce it all here, but the opinions of the two barbers interviewed provide a unique glimpse into popular opinion at the time.

W.C. Inman summed up his feelings and some of the issues with the laws as they stood as follows: “I favor prohibition: I don’t want to see the saloons again. But the way prohibition is enforced is unsatisfactory, for more liquor is used now than when we had saloons…”

His cross-town rival T.M. Newberry was more concerned with snitches than the actual enforcement of prohibition. I sure hope it is a direct quote, cause the phrasing is delightful: “I don’t mind seeing prohibition, but there are some phases of it that I dislike. I hate this use of stool-pigeons to try to convict moonshiners. It gets me to see them mix with drinkers and pretend to be their friends and then turn on them. If moonshiners can be caught legitimately, lets go after them; if not—well, I don’t like it.”[18]

Sources

[1] National Constitution Center – 18th Amendment. https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/amendment/amendment-xviii.

[2] National Constitution Center – 18th Amendment. https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/amendment/amendment-xviii.

[3] “Volstead Act.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volstead_Act

[4] “Volstead Act.” Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volstead_Act

[5] “Dry Bill is Passed Over Veto.” Oregon Statesman 28 Oct 1919 pg 1

[6] “Dry Bill is Passed Over Veto.” Oregon Statesman 28 Oct 1919 pg 6

[7] George, Robert. “Common Interpretation: The Eighteenth Amendment”. constitutioncenter.org. Retrieved January 9,2018.

[8] National Constitution Center – 18th Amendment. https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/amendment/amendment-xviii

[9] “Michigan Wets fight to vote again.” Lancaster Examiner 28 De 1918, page 8 [their bill will] “last until the national war prohibition act takes effect in July.” Also, “Last Wet Day Ends in Nationwide rush to stock up for dry spell.” New York Sun, 1 July 1919 pg 2 [catalogued in newspapers.com under New York Herald, does not match the masthead.]

[10] “Drys Win all Cases before Highest Court.” Oregon Statesman 4 Feb 1914 pg 1; “Progressive’ Covers Ideas” Oregon Statesman 4 Feb 1914, pg 1

[11] “Prohibition in Oregon.” Oregon Secretary of State’s Office, virtual exhibit. https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/highlights/Pages/prohibition.aspx. Makes reference to the Anderson Act enacted by legislature in 1915, taking effect Jan 1916.

[12] See description in the 1917 City Directory which gives receipts from industry.

[13] The 1913 Salem City Directory lists 15 saloons active and two “Brewers” including the Salem Brewery Association

[14] “Brewery can operate in Salem but Saloons are Wiped Out.” Capital Journal 3 Feb 1914 pg 1

[15] https://www.brewerygems.com/salem.htm

[16] “Brewery can operate in Salem but Saloons are Wiped Out.” Capital Journal 3 Feb 1914 pg 1

[17] “What they think of” Oregon Statesman 31 Aug 1928 pg 1 “

[18] “What they think of” Oregon Statesman 31 Aug 1928 pg 1.

*”Salem Dry by a majority of 952 Votes. Oregon Statesman 2 Dec 1913 pg 1

This article appeared in the October 6, 2019 edition of the Statesman Journal. It is reproduced here with citations for reference purposes. It was researched by Kylie Pine.

Leave A Comment