Readers should feel free to use information from this article, however credit must be given to the Willamette Heritage Center and to the author.

By Danielle Strom

In 1844, a strong desire to avoid racial tensions led the Oregon Provisional Government to outlaw slavery in the Oregon Country. However compassionate this may sound, it was closely followed by a ban on the settling of free blacks in the region. Both laws were designed to keep the black population at a minimum and avoid conflict. Despite these decrees, many families brought slaves on their journey west and few, if any, of the slaves were set free upon entering Oregon. Rachel Belden was one of these, and is the first known black woman of Marion County.

[1]

Born in Tennessee in 1829,[2] Rachel was raised as a slave, working in the fields and home of her masters. Like many slaves in that day, Rachel accepted the last name of her first master, becoming Rachel Belden. Around 1840 she became the property of Daniel Delaney, Sr. Preparing to stake his claim in the West, Delaney (also spelled Delany) sold his plantation and all of his slaves to a man in Tennessee. However, Mrs. Elizabeth Magee Delaney was very ill, practically an invalid, and in need of care. To secure a caretaker for his wife, Delaney bought Rachel Belden for $1000.[3] Shortly thereafter, the Delaney family moved to Missouri where they prepared for their journey over the Oregon Trail. When they left, other notable men such as Daniel Waldo and Peter Burnett, and families such as the Nesmiths, Applegates, and Looneys, accompanied the Delaneys while Dr. Marcus Whitman was “their captain and guide.”[4] These were only a few of over one hundred families to start on the Great Migration: the first significant overland trek to make it as far as The Dalles.[5] Mr. and Mrs. Delaney crossed the plains with Rachel and three of their five sons,[6] settling in the Champooick District (later named Marion County) in 1843.[7]

It is possible that Rachel was unaware of the law that declared her a free woman in the Oregon County and therefore stayed with the Delaney family for the next two decades. Besides taking care of the ailing Mrs. Delaney, Rachel did the housework and took care of the garden.[8] Moreover, noted pioneer John Minto later commented on her industriousness as she worked side by side with the Delaney boys in the orchards and fields.[9] Different writers give varied accounts of the character of Rachel’s master. On one hand, he was a caring man, well-liked and hospitable to everyone, including his slaves. A southern gentleman in every way, “Mr. Delany was so highly respected and his good deeds of helpfulness to the settlers that came after him so well known,” that his death caused terrible sadness.[10] Another writer suggests that he did little work himself and “seemed to read his bible chiefly to find in it support for his dominion over the soul and body of his female slave.”[11] Whatever sort of man he was, Rachel lived with him and the family until federal law set her free during the Civil War. During this time, Rachel bore two sons: Newman, born in 1847 (also referred to as Noah), and Jack (also known as Jackson or Jack De Wolf).[12] It is suspected that Mr. Delaney fathered these two mulatto boys.[13]

Even as Rachel was an important first in Marion County, her son Jack played a role in another first, the first murder trial in Marion County. Many knew Daniel Delaney, Sr. as a wealthy man and the temptation of his supposed fortune became too much for George Beale and George Baker. On January 9, 1865, these men painted their faces black, rode to the Delaney property where, to their knowledge, Mr. Delaney was alone. After a brief struggle, they shot Delaney and left him to die. Jack, a well-known

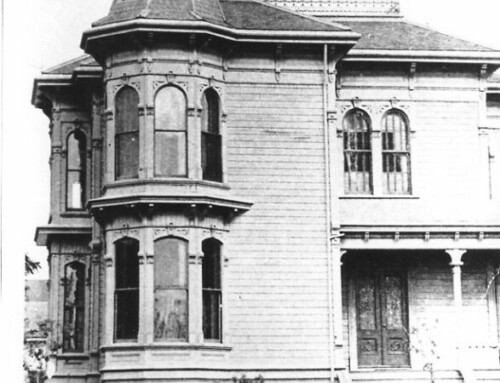

Delaney House – Turner, Oregon. Photo courtesy of Historic Marion 42, No. 2

companion and servant of Delaney, saw the whole episode take place.[14] When authorities later apprehended Beale and Baker, it was the testimony of this young boy that stood strongest against them. Both men were convicted and publicly hung; the first in Marion County to die for a capital offense. Amazingly, the house that was the center of Rachel’s everyday life, and the location of the murder of Daniel Delaney still stands today just outside of Turner.[15]

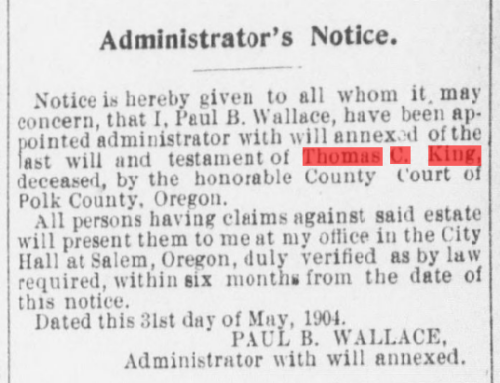

In 1864, Rachel married the widower Nathan Brooks. In March 1865 and again in November of that year, Nathan brought a suit against Mr. Delaney (probably Daniel Delaney, Jr.).[16] Without records, we can only assume it had something to do with Rachel and her sons. One family researcher suggests that it was a “suit on the estate of Delany on behalf of her son for $1000,” but there is no source noted.[17] During this time, the Brooks’ lived on the nearby farm of Daniel Waldo and later moved to Salem. Nathan and Rachel raised two sons of their own, Samuel and Mansfield, along with Jack. Her oldest son, Newman, lived and worked with the Stanley family in East Salem.[18]

Nathan Brooks died in 1874, but Rachel was not left destitute. She worked hard to support her family, and the 1877 tax records show that Mrs. Brooks “owned 144 homestead acres on the west side of the Willamette River near the bend in the river across from Keizer.”[19] Blacks had come a long way since the 1844 Exclusion Act and, even though multiple exclusion laws had been passed over the years, the black population continued to grow. By the 1870 census, Marion county had the second largest population of blacks and mulattoes in Oregon after Multnomah County.[20] Rachel was just one of these. From 1902 on, she is included in the Salem and Marion County Directory, showing her acceptance as part of the community. She resided near “w s Commercial [and] n Mill Creek” for several years, then is listed in the 1909-1910 directory as boarding at the corner of Miller and Fir Streets. Rachel died October 12, 1910 and is buried in an unmarked grave in the Delaney plot at Pioneer Cemetery.[21]

From what little we know of her, Rachel Belden Brooks must have been an amazing woman. As the first black woman of Marion County, she undoubtedly felt alone and isolated. Yet she somehow moved beyond her restrictions, and, as the Book of Remembrances of Marion County notes, became “a familiar figure about the streets, known as Aunt Rachel Brooks.”[22]

[1] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

[2] Oregon Pioneer Association, Pioneer Index of the Oregon Historical Society.

[3] McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: a History of Blacks in Oregon. Portland, OR: The Georgian Press, 1980.

Several sources agree on this price, however the Pioneer Index at the Oregon Historical Society Research Library lists the sum as $550.

[4] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

[5] Hayes, Matt. “Turner’s Delaney House.” Historic Marion 42, no. 2 (Spring/summer 2004): 11-12.

[6] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927. Minto, John. “Antecedents of the Oregon Pioneers and the Light These Throw on Motives.” In Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, ed. Fredrick George Young, 38-63. Salem, OR: J.R. Whitney State Printer, 1904.

Some sources suggest they brought all five sons with them to Oregon, but other records show that this is unlikely.

[7] Oregon Pioneer Association, Pioneer Index of the Oregon Historical Society.

[8] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

[9] Minto, John. “Antecedents of the Oregon Pioneers and the Light These Throw on Motives.” In Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, ed. Fredrick George Young, 38-63. Salem, OR: J.R. Whitney State Printer, 1904.

[10] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

[11] Minto, John. “Antecedents of the Oregon Pioneers and the Light These Throw on Motives.” In Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, ed. Fredrick George Young, 38-63. Salem, OR: J.R. Whitney State Printer, 1904.

[12] McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: a History of Blacks in Oregon. Portland, OR: The Georgian Press, 1980.

Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

Green, Virginia. “Hidden Citizens: Blacks in Salem Through the Years.” Historic Marion 40, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 1-5.

[13] McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: a History of Blacks in Oregon. Portland, OR: The Georgian Press, 1980.

Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

Green, Virginia. “Hidden Citizens: Blacks in Salem Through the Years.” Historic Marion 40, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 1-5.

[14] McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: a History of Blacks in Oregon. Portland, OR: The Georgian Press, 1980.

[15] Hayes, Matt. “Turner’s Delaney House.” Historic Marion 42, no. 2 (Spring/summer 2004): 11-12.

[16] Oregon Statesman 20 March 1865 and 4 December 1865

[17] Flora, Stephanie. Emigrants to Oregon in 1845. www.oregonpioneers.com/1845.htm (accessed June 2009).

[18] Green, Virginia. “Hidden Citizens: Blacks in Salem Through the Years.” Historic Marion 40, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 1-5.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Minto, John. “Antecedents of the Oregon Pioneers and the Light These Throw on Motives.” In Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, ed. Fredrick George Young, 38-63. Salem, OR: J.R. Whitney State Printer, 1904.

[21] Green, Virginia. “Hidden Citizens: Blacks in Salem Through the Years.” Historic Marion 40, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 1-5.

[22] Steeves, Sarah Hunt. Book of Remembrance of Marion County, Oregon: Pioneers 1840-1860. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1927.

Leave A Comment