By the President of the United States of America: A Proclamation…That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United states, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts as they may make for their actual freedom…

Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863

Five years after these words were enacted, they were read in a loud, clear voice by Daniel Jones to a large crowd gathered as part of Salem’s Emancipation Jubilee.[1] The son of a Maryland slave who had escaped to Pennsylvania to start a new life and family,[2] Jones, and his fellow African American Salemites, came together to commemorate and celebrate the anniversary of the enactment of these words with prayer, poems, singing, dancing, orations, and food.[3]

The proclamation itself didn’t end slavery. You’ll note the text is carefully worded to apply emancipation only to people in bondage in states in “rebellion.”[4] Abolition of slavery in the U.S. would require a further constitutional amendment, resolution to a long and bloody war, and, as the newly inaugurated federal holiday Junteenth is teaching us, additional military orders.[5] But for six of the men and women gathered in Salem that New Year’s Day in 1868, these words had marked the granting of their freedom.[6] I wish I could list their names here with confidence, but outside of the presenters named in the scant newspaper coverage of the event, there is no documentation of who actually attended.

While the newspapers captured the poignancy of the event, they are not as generous with what one might consider the most important details. There is a beautiful piece in the Salem Daily Record on January 4, 1868 detailing how one woman had “…furnished a cake [for the Jubilee celebration], on the frosting of which was traced in rude letters, by her hand, ‘Remember her who was born a slave,’ alluding to her own case. Although of middle age, she has learned to read and trace those rude characters since her emancipation.” The woman’s moving story of resilience is ironically (and frustratingly) amplified by the article’s author only identifying her as “A Colored woman.”[7]

Emancipation Jubilee Celebrations

The first Emancipation Jubilees took place on the eve of the president’s proclamation in 1863. It wasn’t a surprise the proclamation was coming. Lincoln had announced it in September of 1862 and indicating January 1st as the date the proclamation would go into effect.[8] A vigil was set up at the Shiloh Presbyterian church[9] in New York City.[10] Similar to the Salem celebration five years later, there were prayers, speeches and songs to celebrate the occasion during the day.[11] Emancipation Jubilee celebrations would be held in cities from across the country, from Washington, D.C. to Oswego, New York in the years to come.[12]

Salem’s Celebrations

Newspaper records are all I have found to document Emancipation Jubilee celebrations in Salem and they are a bit spotty and difficult to access. By the time of this article’s deadline, I had found documentation for celebrations of five Emancipation Jubilees held January 1st in Salem between 1868 and 1879,[13] and mentions of three more held in Portland. Nearly all of the celebrations are styled as a statewide or region wide event and the Portland celebrations were held in years where there was no mention of Salem celebrations, suggesting there may have been some coordination between communities in the planning.[14] Explicit documentation is given of folks coming up from Albany via steamship to participate in the 1868 Salem celebration.[15]

It is difficult to determine where in Salem the first celebration was held. Both extant newspaper articles describing the event use quotation marks around the venue description. One calls it the “’Church’ School House” and the other the “’Methodist Church South.’” I’m sure these nods were probably understandable to readers at the time, but a bit mystifying in the present. The 1871 Salem City Directory does list a South Salem Methodist Church with a capacity to seat 300 people, but again in maddening vague detail doesn’t list where in South Salem it was (but just in case you were wondering, their Sunday school library contained over 301 books).[16] Mentioning a “school house” here is interesting, because at the time the African American community of Salem was renting a room in order to have a school that their children could attend, the city’s schools having barred their children entry (even though they were paying the taxes that supported the city’s school system). Fed up, parents raised enough money to hire a teacher and rent a room to provide their children with an education.[17]

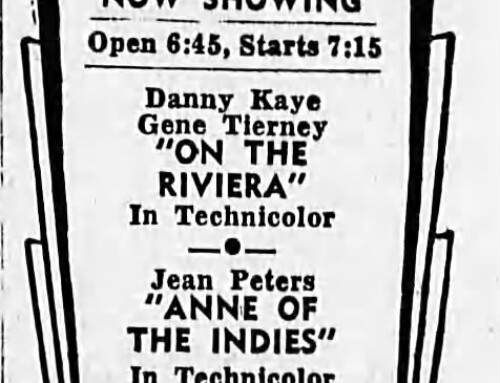

The 1872 celebration was held at the Reed Opera House and the 1879 event at the Bayless family home in Piety Hill on the corner of Marion and Summer Streets.[18] The program seems to be pretty consistent over the years. The recitation of the proclamation was combined with prayer, song, poetry readings and lectures, music, dancing and food. The festivities were open to all, and while the tone in the Salem papers is very positive, the rampant prejudice of the time seeps through. Describing the 1868, event the Salem Daily Record hints at the scorn many Black Salemites had to deal with on a daily basis, in addition to passively reinforcing the divide with their own “us vs. them” language: “Many of our [”our“ taken in this context meaning white] citizens of both political parties were present, and we doubt if there was one among them all who failed to respect this effort of colored citizens to show respect for the day from which they date the freedom of their race in this nation. It is to be regretted that many who scorn them were not there to see how they honor freedom and love to claim its privileges.”[19] The Albany paper with the position-revealing name (State Rights Democrat) was outright hostile. One editor spent several columns on what can only be described as a venomous racist diatribe after travelling to Salem on the same boat with Albany contingent to the Emancipation Jubilee in 1868[20] clearly expressing his opinions on equality. This pattern is repeated in the two-line description of the 1872 event, which utilizes a demeaning affectation in the spelling of the names and titles of the presenters.[21]

There are some bright spots of recognition, too. The Oregon Statesman in describing the 1870 Emancipation Jubilee celebration noted that it was “the anniversary of the greatest event that has happened in our national history since the Declaration of Independence, and perhaps including that memorable occasion. That document simply set forth that three million of free people did thus throw off their allegiance to Great Britain. The Emancipation Proclamation declares that four millions of slaves, property, chattels, were free men and women. To that race it is the first bright spot on their American history; to others it is the day which saw a foul stain wiped from the escutcheon of the nation.”[22]

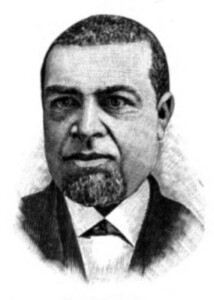

The Reverend Daniel Jones

Reverend Daniel Jones. Lithograph as published in William J. Simmon’s, DD. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. Cleveland: Geo. M. Rewell & Co., 1887

At the time Daniel Jones read the words of the Emancipation Proclamation at Salem’s first Emancipation Jubilee, he was a barber, a profession he had learned in Philadelphia after leaving home at age 10. When he was 17, he decided to become a sailor, and at age 19 he became a ‘49er panning for gold in California and Oregon before settling in Jacksonville, Oregon, where he married his wife Annie and started his own business.[23] An advertisement for the shop he set up in Jacksonville reads: ”Barber Shop. Opposite the Post Office. Shaving, Hair Cutting, Shampooing and Curling. Hair Dyed either black or brown…He also has a laundry attached to his establishment, and is prepared neatly to wash, iron and promptly deliver Gentlemen’s Clothing.”[24] By 1868,[25] Jones and his family, now including two sons and a daughter, had moved to Salem.[26]

Four years later, the newly ordained Methodist Episcopal Reverend Daniel Jones gave the oration at the Jubilee. In the intervening years Rev. Jones enrolled at Willamette University, his biography stating he was the first African American student at the school,[27] and planted a church at the corner of High and Marion Streets.[28]

Jones left Salem in 1873 when he was transferred to a pastorate in Newark, New Jersey, but not before serving as a delegate representing the State of Oregon at the 1873 Civil Rights Convention[29] in Washington, D.C.[30] Jones would serve churches in Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Kentucky before being promoted to the position of presiding elder. In addition to his religious duties, he continued to advocate for civil rights and education until his death in 1891.[31] He served on endowment committee of the Central Tennessee College,[32] an historically Black college in Nashville,[33] and lobbied the Kentucky State Legislature on education policy, edited a local newspaper and served as a correspondent for others.[34] His biographer wrote of him “His pen and voice are never silent…”[35] May the same be said of all of us in the continuing work of freedom.

This article was written by Kylie Pine. It appeared in the Statesman Journal Newspaper in January 2022. It is reproduced here with full citations and additional contextual information for reference purposes.

Learn More

Read the Emancipation Proclamation at the National Archives online exhibit here.

Read the Lyrics of the Rally Round the Flag song sung at the first celebration here.

Transcriptions of Selected Sources

1868 Salem Emancipation Jubilee Celebration

“Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg 2, Col. 1. Accessed via microfilm collection at the University of Oregon Knight Library.

A very respectable company of colored people of Salem, Albany and the surrounding country assembled Wednesday evening at the “Church” School House, so called, to celebrate the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Lincoln, January 1, 1863. Many of our citizens of both political parties were present, and we doubt if there was one among them all who failed to respect this effort of colored citizens to show respect for the day from which they date the freedom of their race in this nation. It is to be regretted that many who scorn them were not there to see how they honor freedom and love to claim its privileges. To make the appropriateness of the services complete, there were present six persons who were made free by the Proclamation.

The exercises were conducted entirely by themselves. A. Bales, a blacksmith, presided. Wm. Johnson opened the meeting with an earnest prayer. A young girl, Martha Johnson, of Albany, read a poem, during the exercises, with a considerable degree of taste. A singing club, of ten persons, made good music of the national anthem, “Rally round the Flag,” and several other national hymns and glees. The melodeon was well played by a colored man; the address by Dan Jones was brief, pertinent to the day, and in good taste. He also read the Emancipation Proclamation very well, and it was listened to with great attention. The scene at the singing of the Battle Cry of Freedom – “Rally round the Flag, Boys,” –called out all the enthusiasm of the impulsive race. Every voice shouted it, hand were wildly waved toward the flag, which formed a principal ornament of the room, and there could not have been an unmoved heart in the audience.

The evening wound up with a social dance and supper, at which a few persons only remained to protect them from any intrusion. A gentleman used to good fare, says a better “spread” was never been made in this State. The affair was in every way creditable to those concerned.

“Emancipation Fete” American Unionist 06 Jan 1868 pg 1. Accessed through the microfilm collection at the University of Oregon Knight Library.

The colored people of the Willamette Valley had a very imposing celebration at the “Methodist Church South,” on New Year’s Day. The place was appropriate, and the ceremonies were conducted with great dignity, heart-felt joy and grateful enthusiasm. The proceedings, in brief, were as follows, A. Bales[sic], presiding: Prayer, by Wm. Johnson, Reading the Proclamation, and address, by Daniel Jones; poem, read by Miss Martha Johnson, of Albany; singing by glee club, with melodeon accompaniment, and the congregation joining in the stentorian outcry of gladness. The several performances were most credible, earnest and in good taste. A dancing party and supper in the evening concluded the day’s festivities. For the credit of the white race, we wish that a similar number of constitutional Democrats could be got to gether[sic], on a fete-day and be made to conduct universally with equal intelligence, decorum and respectability; but the thing is impossible, in a region where whisky-shops are accessible. And yet, copperheads fresh from the wallow, perhaps with the marks of hand-cuffs on their wrists, and with hair but recently cropped at the expense of the commonwealth, affect to despise black people! And wherefore? In all the histories of great nations, ours alone excepted, it does not appear that a black or tawny skin, or a crisp hair or a globule of African blood, ever obstructed its possessor in the pursuit of military renown or in his ascent to civic distinction. Do our Democratic “Caucasians” know anything about ancient Afric civilization, or of the swarthy people who once inhabited the country of the Euprates [sic], and left the wondrous monuments of their intelligence? Perhaps not.

Citations

[1] “Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg. 2, Col. 1. (MICROFILM UO KNIGHT LIBRARY); “Emancipation Fete” American Unionist 06 Jan 1868 pg. 1. UO KNIGHT LIBRARY MICROFILM Collection;

[2] Simmons, William J., D.D. Men of Mark: Eminent Progressive and Rising. Cleveland: Geo. M. Rewell & Co., 1887, pg 583.. (Accessible via HathiTrust.org)

[3] “Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg 2, Col. 1. (MICROFILM UO KNIGHT LIBRARY); “Emancipation Fete” American Unionist 06 Jan 1868 pg 1 UO KNIGHT LIBRARY MICROFILM;

[4] You can read the entire text of the proclamation at the National Archives Website. A listing of the places considered at the time of Lincoln’s announcement of the proclamation in September 1862 is also published in the Oregon Sentinel (Jacksonville, Oregon) 10 Jan 1863 pg. 3 as part of the coverage of the Emancipation Proclamation (accessible via the UO Oregon Historic Newspaper database). Included in the list of places in open rebellion include: “Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana [excepting the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemine, Jefferson, St. Johns, St. Charles, Assertion, Bayon La Fourche, St. Mary, ST. Martin, and New Orleans, including the city of New Orleans], Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Virginia (excepting forty-eight counties designated as Western Virginia, and other counties of Berkley, Accomae, North Hampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth], which excepted parts are left for the present as if this proclamation was not issued.” I.e. for anyplace not on this list the emancipation did not apply.

[5] There is a lot of source material for this, but I found this article the most clear and comprehensive. Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “What is Junteenth”. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/what-is-juneteenth/. Accessed 1/17/2022.

[6] “Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg. 2, Col. 1. (MICROFILM UO KNIGHT LIBRARY). “To make the appropriateness of the services complete, there were present six persons who were made free by the Proclamation.” See also: Corvallis Gazette 11 Jan 1868 pg 2 . “Six persons were present who were made free by the Proclamation of 1863.”

[7] “A Colored Woman.” Salem Daily Record 04 Jan 1868 pg. 3. (UO KNIGHT LIBRARY MICROFILM)

[8]“Transcript of the Proclamation.” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html

[9] “Grand Emancipation Jubilee.” New York Times. 01 Jan 1863 pg. 8

[10] MAAP Project Columbia university provides attribution of this Church to New York City and some history. https://maap.columbia.edu/place/37.html

[11] “Grand Emancipation Jubilee.” New York Times. 01 Jan 1863 pg. 8

[12] Singer, Alan J. New York’s Grand Emancipation Jubilee: Essays on Salver, Resistance, Abolition, Teaching and Historical Memory. Albany: SUNY Press, 2018. Some examples: “Emancipation Jubilee” New York Times 2 Aug 1865 pg. 1.; “Latest News” Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield Mass) 02 Jan 1868 pg. 2; Emancipation Jubilee. Boston Evening Transcript. 02 Jan 1868 pg. 4; “Washington Items.” Alexandria Gazette 28 Mar 1868 pg.3.; “Emancipation Jubilee” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 31 Dec 1868 pg. 5

[13] 1868— “Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg 2, Col. 1. (MICROFILM UO KNIGHT LIBRARY); “Emancipation Fete” American Unionist 06 Jan 1868 pg 1 UO KNIGHT LIBRARY MICROFILM; 1870 — “Emancipation Day.” Oregon Statesman 01 Jan 1870 pg 3; “Emancipation Day.” Oregon Statesman 04 Jan 1870 pg 2; 1872—“Anniversary of Emancipation.” Weekly Oregon Statesman 10 January 1872 pg 1; States Rights Democrat (Albany) 22 Dec 1871; 1876—“Anniversary Ball.” Weekly Oregon Statesman 08 Jan 1876; 1879 — “Celebration” Willamette Famer 3 Jan 1879

[14] Portland celebrations were held January 1, 1869, 1871, and 1874. See “Sixth Anniversary of Emancipation.” Albany Register 26 Dec 1868 pg 2; “General News” Oregon Weekly Statesman 04 Jan 1871 pg 1; “State News” Weekly Oregon STatesman. 09 Jan 1874

The former of which states: “The Oregonian says the colored people of Portland are making extensive preparations to entertain guests from other parts of the State, and it is expected the celebration will be rather imposing.”

[15] “What is Negro Equality.” States Rights Democrat 4 Jan 1868 pg 2. Be warned, this article is difficult to read. The writer, while describing his trip via boat to Salem, goes on a racist diatribe.

[16] 1871 Salem City Directory. Copy can be accessed here: https://www.willametteheritage.org/1871-salem-city-directory/.

[17] See discussion of Salem’s segregated schools in Bell, Susan N. “Salem’s Colored School.” Historic Marion Salem: Marion County Historical Society Spring 2002, pg 8. It should be noted I am indebted to the author of this article for highlighting the Emancipation Jubilee celebrations in Salem.

[18] “Celebration” Willamette Famer 3 Jan 1879. The newspaper lists home as being on Piety Hill: “join the festivities on the occasion, at Bayliss’ house, on Piety Hill.” Although the 1880 Salem City Directory lists the residence at the “cor Marion and Winter” streets, this appears to be a typo. The Bayless family owned property at the SE corner of Marion and SUMMER Streets. See Marion County Deed Records Book 22 page 340 (Accessible via Family Search): which describes purchase of a property consisting of lots 9 and 10 in Block 87 of the City of Salem. Compare to the Plat of Salem, Oregon accessible via Marion County Surveyor’s Graphic Index here, which confirms Lots 9 and 10 of Block 87 are located at the SE corner of Marion and Summer Streets.

[19] “Emancipation Jubilee” Salem Daily Record. 3 January 1868 pg 2, Col. 1.

[20] “What is Negro Equality.” States Rights Democrat 4 Jan 1868 pg 2

[21] State Rights Democrat (Albany) 22 Dec 1871 pg 2.

[22] “Emancipation Day.” Oregon Statesman 01 Jan 1870 pg 3

[23] Simmons, William J., D.D. Men of Mark:Eminent, Progressive, Rising. Cleveland: Geo. M. Rewell & Co., 1887 pp 583-584. (Accessible via HathiTrust: #695 – Men of mark : eminent, progressive and rising / by William J. … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library)

[24] Advertiesement. Oregon Sentinel 22 June 1861 pg 2.

[25] Evident (I think) that the family was here by the 1868 Jubilee Celebration.

[26] See 1870 US Federal Census.

[27] Simmons, William J., D.D. Men of Mark: Eminent Progressive and Rising. Cleveland: Geo. M. Rewell & Co., 1887, pg 583.. (Accessible via HathiTrust.org); Attendance at Willamette University seems to be confirmed in the 1870-1871 Willamette University Bulletin (accessible online through Willamette University Archives and Special Collections here: https://libmedia.willamette.edu/cview/bulletinscatalogs.html#!doc:page:bulletinscatalogs/BulletinsCatalogs1870/jp2/6/15/0/16,19,22,27), pg 14.) which lists Prepatory Student Daniel Jones of Salem.

[28] 1872 US City Directory, pg 73, pg 43. Colored M.E. Church. – Place of meeting, corner of High and Marion streets. Organized April 17th, 1871, with 11 members. Rev. David [sic] Jones, pastor.

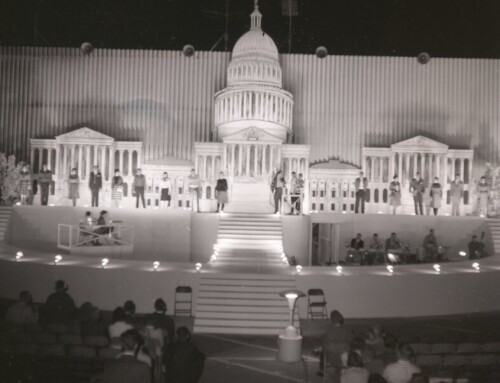

[29] National Civil Rights Convention Information here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1873_National_Civil_Rights_Convention. Also referred to as the National Equal Rights Convention. See Library of Congress Photo by w. Ogilvie here. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004671620/

[30] Note: Weekly Oregon Statesman 14 Jan 1873 pg 2describes transfer. Simmons, William J., D.D. Men of Mark:Eminent, Progressive, Rising. Cleveland: Geo. M. Rewell & Co., 1887 pp 583-584, describes transfer and service to delegation.

[31] Used to Live Here. Oregon Statesman 05 Apr 1892 pg 1; Death of Colored Minister. Courier Journal (Louisville) 26 Dec 1891

[32] 1890 Catalog Central Tennessee College.

[33] Walden University. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walden_University_(Tennessee)

[34] Simmons, 578.

[35] Simmons, 578.

Leave A Comment