When Salem was “Wet”: Early Salem Saloons

“In 1869, Salem’s Council adopted an ordinance “Relating to Common Drunkards: …. any person in the habit of becoming grossly drunk, and had kept up such a habit for period of one month, the Recorder shall declare such a person a common drunkard.”

One of the first items of concern in Oregon’s governmental history, reflecting the religious and conservative character of its earliest settlers, was a law prohibiting liquor in the new territory. Proposed and passed in 1884 by the Legislative Committee meeting at Willamette Falls (Oregon City), the Act prevented “the introduction, sale, and distillation of ardent spirits in Oregon.” This prohibitory act was superseded in 1845 by what was hoped to be a rather more constitutional law: the imposition of a hefty license fee on anyone contemplating the sale of intoxicating beverages. Despite Provisional Governor Abernathy’s veto, the bill passed and became law on the 18th of December, 1846.

1915 c., Saloon and Dance Hall – “Cherrian Cherrin Company” Salem, Oregon. Crowd of people with back bar in back of photo., WHC Collections 0063.001.0073.002.07

The licensing fee was set at $200 per year, in a cash-poor society, rendering it nearly impossible to open any kind of establishment dispensing liquor. That all changed by 1849 when gold dust from the California mines began to drift northward. In July of 1850, the first license to sell liquor in Salem was issued to “O.P. Riley” (Philip O’Riley). He paid the fee and, according to later licensing provisions, offered security bonds on the condition that he would “keep an orderly house and allow no unlawful gaming or riotous conduct in or about” the premises. Within a few months, O’Riley had turned the enterprise over to James Force.

Named appropriately the El Dorado Saloon, the tavern was located in North Salem, near the mills bought by Force’s brother John. By October of 1852, the establishment was in the hands of “Plomanden” and Isaacs. Following the designation of Salem as Territorial capital, political affairs transferred to the burgeoning city on the Willamette. This required that accommodations for Legislators and executives arriving to transact business in the new capital be provided; one of the first to capitalize on this necessity was Joseph Holman, who opened his Holman House in 1851. The “Old Holman Building” had been built previous to 1850 to the west of Commercial Street on Ferry. Holman operated a store and hotel expressly for the reception of travelers to Salem.

“Vic’s” Saloon held forth at the Holman House in its early days to cater to the thirsts of travelers and Early Territorial Legislators. Run by one of the most colorful characters in early Oregon history, Victor Trevitt – – known for his very “original and spicy humor” – – the watering hole even had a “boll alley” for the diversion of its patrons. Since Trevitt also served as Clerk of the Territorial House from 1851-1855, he was intimately acquainted with most members of the Legislative Assembly, and he may have been one of the “association of gentlemen” who published the first newssheet ever issued at Salem – – the Vox Populi – – which dealt exclusively with Legislative matters in a most irreverent manner; it was published at the Holman House, and the material contained in the early newspaper probably originated over drinks and cigars at Vic’s. James W. Nesmith took over the saloon and bowling alley when Trevitt left for Eastern Oregon.

Another early saloon, in what would become downtown Salem, was the Nonpareil; its exact date of establishment is unknown, but it was advertising ice for sale in the summer of 1854. Housed in the Montgomery Building on the east side of Commercial Street just south of State Street, the saloon was in existence by the summer of 1853 since other businesses advertised their location as “next to” or “just south of” the Nonpareil. This saloon may have been operated by Elias Montgomery, builder of the business house that bore his name, as he was granted a license to sell spirituous beverages in July of 1855.

On that same day, Thomas B. Newman applied for and received a license to keep a “Bolling Alley and Billiard Table.” It could be that the Nonpareil was a billiard saloon (with a bar on the side), as the popularity of that form of entertainment was at its zenith in the early 1850s. And use of the term “saloon” could cover a multitude of functions: a barber shop of that time was called a “Tonsorial Saloon.”

By 1858, according to Kuchel and Dressel’s lithograph of the Salem scene, three saloons were prominent enough to include in their illustrations of residences, churches, and business houses. The “Gem Saloon” was the only one shown as part of a hotel, the Union House. That hotel had an interesting history of its own, being a combination of the first store in Salem (that of William Cox and Company, established in 1848) and a blacksmith shop erected next door. When the Coxes closed their store in 1853, the two buildings were joined to become the Union (signifying the fact of its having once been two separate structures).

Here, at the northeast corner of Commercial and Ferry, Patrick D. Palmer kept the bar. Palmer’s bar also sported a billiard table. The Union House burned in May of 1863; when it was rebuilt, the barroom became the Magnolia Saloon and, in 1871, was leased to Mrs. Eliza Bernant, the only female proprietor of a saloon in Salem to that date.

Perhaps the longest running saloon in Salem’s history was the Belvedere, on the west side of Commercial Street between State and Ferry Streets. Also pictured in Kuchel and Dressel’s 1858 Salem view, the saloon was built by the Plamondon brothers, Eusebe M. and Francis F., in the summer of 1854, and was often referred to as “Plum’s” Belvedere. Their establishment featured both billiards and a “Bolling alley.” Even though it burned in April of 1866 – – supposedly the work of an arsonist – – it was rebuilt in another location and was going strong near the turn of the twentieth century.

The last of the three pictured saloons in 1858 was possibly the most infamous: John “Patcheye” Byrne’s Crystal Saloon (not to be confused with another notorious tavern, John “Sandy” Burns’ North Star Saloon, which was of a later vintage). The Crystal must have been close to the Union House for, when that hotel burned in May, 1863, the fire had been deliberately set in the rear of the Byrne’s saloon; his loss was $5,000. P.D. Palmer, another substantial loser in the fire, swore if he found out Byrne had fired his own saloon, he (Palmer) “would put a patch on his other eye.” Byrne rebuilt, apparently, for he was one of the five saloon keepers listed in Salem’s directory for 1867. The other four were: W.L. Morris Brook Saloon, Robert Meinkey’s Magnolia Saloon in the Union Hotel, the Belvedere, and George Spong’s North Star Saloon.

In 1869, an innovation in saloon entertainment made its debut at the North Star Saloon: “hurdy-gurdy” girls, the first ever seen in Salem. These dancers may have come from Maggie Gardner’s establishment on the east side of Liberty Street between Court and State Streets. “Madame Maggie and her girls” had become a Salem fixture ever since her arrival in 1867. And the fact that lightning didn’t immediately strike the historic old building was cause for amazement since the structure was built by the Reverend Lewis H. Judson for his family and later served at the cradle of the Pacific Christian Advocate, first published in 1855 on the premises. A short-distance move to Court Street between Commercial and Liberty Streets, and the addition of a false front, transformed the old home into a saloon whose reputation for nickel beer and free fisticuffs made John “Sandy” Burns’ place a hangout for the rowdy element in Salem.

When the Opera House on Liberty and Court was completed in 1869, it also offered spiritous beverages for the clientele: O.H. Smith’s Opera Saloon. Joseph Bernardi’s Capital Saloon on the south side of State Street dispensed wines and liquors prior to 1871, as did J. Adkins and L..J Stone in the Pony Saloon, also on State Street. Robert Bean’s Oriflamme Saloon opposite the Chemeketa House was in direct competition with O.H. Smith’s Chemeketa Saloon in that hotel. By this point in time, several hotels were established in both North and downtown Salem, each having a barroom or tavern to slake the thirst of its clients.

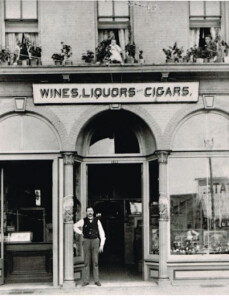

1890 c., Man standing in doorway of his shop (identified as Paulus Saloon). Large sign advertising wines, liquors and cigars is above doorway. Baby in middle window and woman in window above right over the saloon. Man is Chris Paulus, Woman is Elizabeth Nees Paulus and baby is Fred Paulus, WHC Collections 2013.013.0091

There were, in addition to the thirteen saloons operating in Salem in 1871, three breweries: the Pioneer begun by John Brown and Henry Hageman in 1862, the City of Salem Brewery established by Thomas Green in 1866, and the Pacific in North Salem, established also in 1866 by Lewis Westacott. Salem offered, indeed, a plethora of “adult beverages” to be consumed!

By 1889, Commercial Street in the three blocks between Trade and Court Streets was a veritable drinker’s paradise with nine bars or saloons on either side of the street; six years later, there were an even dozen saloons in that short space, and State Street between Water and High Streets featured another six. Understandably, with all this imbibing going on, the civil authorities were hard-pressed to keep the peace. Every issue of the local paper carried a notice of some “disturber of the peace” brought before the City Recorder to answer for his misbehavior.

In September of 1869, Salem’s Council had adopted an ordinance “Relating to Common Drunkards: on petition of 20 residents of Salem to the City Recorder that any person is in the habit of becoming grossly drunk, and had kept up such a habit for period of one month, the Recorder shall declare such a person a common drunkard.” Further, “it shall not be lawful for any person to sell, give, or in any manner assist such drunkard to obtain any wine, spirituous, or malt liquors.”

To further emphasize the problem, in the 1872 City Recorder’s report, he cited the arrest of 81 persons for drunkenness in the previous eleven months. The usual penalty for such public displays of inebriation was a fine and/or a night in the City jail to “sleep it off.” At the Salem Council meeting of 22 April 1869, a committee was appointed to recommend a plan for building a new City jail. This was built on Liberty Street below State Street to replace the old wooden calaboose constructed in 1853 on Ferry Street between Church and High Streets. (The new lock-up served its purpose until 1894 when the jail facilities became part of the new City Hall.)

The 1870s was period of growing agitation on the part of Salem society against the evils of drink. The severity of the problem was exemplified by a suit brought by the Marion County Commissioners against Robert W. Hill at its April, 1871, term; the defendant was accused of wasting $8,000 of his estate on excessive drinking and idleness, leaving his wife and two small children as potential charges on the County. To remedy the situation, a guardian was appointed to preserve what was left of the young man’s property and see to it that Hill reformed his ways.

A Women’s Temperance Prayer League had been organized in Portland early in 1874 and set about harassing – – by prayer and hymns – – patrons of various drinking establishments in that city. Nothing quite so militant had been formed in Salem by that date but, as early as 1853, Salem had an active organization of the Sons of Temperance; in May they urged all “Christians, philanthropists, and patriots” to join a general rally “to help stay the tide of drunkenness and desolation.” This organization died out in 1858 but was reorganized that year as part of the Oregon Territorial Temperance Association.

By the Spring of 1865, an ordinance to close all Salem businesses on Sunday – – effective May 1st of that year – – was issued. This new act, Section 653 of the Criminal Code, proscribed Sunday opening of any “store, shop, grocery, boll alley, billiard room, tippling house, or any place of amusement . . .” Exceptions to this ordinance were grocery stores which could be open until nine a.m., drug stores until ten a.m., and restaurants serving food to be eaten on the premises until ten a.m. on Sundays. Fines to be imposed on those disobeying the order were set at $5-$50.

This ordinance failed to accomplish its purpose, but another attempt in the Spring of 1874 – – a voluntary Sunday closing law – – gained the support of a goodly proportion of Salem’s businessmen, thought only a handful of the town’s tavern keepers.

On the National scene, a Prohibition Party had been organized in 1869; by 1874, the Women’s Christian Temperance union was in operation throughout the country. While Salem can lay claim to no such aggressive reformers as Carrie Nation and her ax-wielding, saloon-busting tactics, apparently Salem’ local temperance societies were a force to be reckoned with if this notice by one saloon keeper is any indication:

Salem, November 7, 1879

Notwithstanding the frantic efforts of certain interested parties to

close up the Granger Saloon, it’ doors are again opened, and I

am happy to state to my customers that no change whatever has

been made in either liquors or cigars.

W.B. McMahan

By May of 1909, the Prohibitionists had gained sufficient influence to force a vote in the City Council making Salem a dry town. Five years later, the whole state had voted “dry”, joining 31 other states who had so voted by 1919 when Constitutional Amendment 18 became the law of the land, and alcohol of any kind was prohibited.

For all intents and purposes, Prohibition closed down all of Salem’s saloons but, for the nearly seven decades that had flourished in the town, their presence on City streets had provided a constant source of new items for the local paper and fodder for countless sermons in churches throughout the City. For the 14 years Prohibition was in effect, the liquor traffic didn’t halt but merely went underground with bootlegging and moonshine stills setting up operations in the Valley, but that is another whole chapter in Salem’s history.

Researched and written by Sue Bell

Bibliography:

Illustrated Historic 1 Atlas Map of Marion and Linn Counties, Oregon (S.F.: Edgar Williams & Co., 1878), pp. 18-19.

Contemporary newspapers are of little use during this early time period, as it seems Asahel Bush accepted no saloon advertising, or the owners felt it was a needless expense; therefore, unearthing details on early Salem saloons necessitated the use of sources such as:

Marion County Miscellaneous Records (hereafter MCMR),

Marion County Commissioners Court Journals (hereafter MCCCJ),

Marion County History (hereafter MCH) issues, and Salem directories for various years.

Sources for the El Dorado Saloon were MCMR, Vol. 1, p. 232; MCCCJ, Vol. 1, July, 1851;

OR Census- -1850; Lewis Hubbel Judson, Sketches of Salem, MCH, Vol. 2, p. 47.

Salem Daily Record Newspaper, 12 June 1867, 3:1; MCMR, Vol. 1, p. 123; Oregon Statesman Newspaper, 16 Dec. 1851, 2:5.

CMMMJ, Vol. 2, p. 154; ad in Oregon Statesman, 25 July 1854, 3:3.

MCCCJ, Vol. 2, p. 102; Capital Journal Golden Anniversary & Capitol Dedication Edition, 2 July 1938, 8:1; MCMR, Vol.2, pp. 140-141 and Vol. 3, p. 495.

MCCCJ, Vol. 2, pp. 101, 129; Daily Oregon Statesman, 10 Aug. 1895, 4:4

- Henry Brown, Sketches of Salem from 1851 to 1869, MCH, Vol. 3, p. 22; Hal D. Patton’s Fiftieth Anniversary 12 Jan. 1922, p. 31.

Ben Maxwell, Salem in 1869: A Year of Transition, MCH, Vol. 3, pp. 27-28; Lewis Judson, Reverend Lewis Hubbel Judson, MCH, Vol. 4, pp. 21-24.

Salem Directory 1871 & 1872, p. 60; Maxwell, op. cit., p. 28.

Salem Directory 1872, City Recorder’s reports.

Malcolm H. Clark, Jr., et al, The War on the Webfoot Saloon & Other Tales of Feminine Adventures (Ptld: Glass-Dahlstrom Printers, 1969), pp. 3-23; Oregon Statesman, 21 June 1853, 3:3.

Daily Oregon Statesman Newspaper, 11 Apr. 1887, 3:2.

The Daily Talk, 7 Nov. 1879, 3:3.

Daily Capital Journal newspaper, 17 May 1909, 1:5.

Salem Public Library, Ben Maxwell Photo Collection

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment