Oregon State Capitol and the Capitol Mall

The original plat of Salem was laid out in 1846 by William H. Willson, a former lay member of the Methodist Mission. Distinctive characteristics of Willson’s plat were its broad avenues ninety-nine feet in width and generous blocks about 300 feet square.

At the heart of the plat was the larger of two public squares, a continuous open space three blocks long known as Willson Avenue. Salem’s most important institutions, including the Methodist Church and the Oregon Institute (forerunner to Willamette University) were located here.

Government buildings which initially stood at the east and west ends of Willson Avenue eventually filled all but one block of the central public space set aside on the original plat.

In this east-west arrangement of government buildings along Willson Avenue, the subtle slope of the land slightly elevated the Territorial and State capitols at the head of the avenue above the Marion County Courthouse at the west, or lower end.

The capitol dominated other government buildings and was surrounded by prominent religious, educational, and public buildings.

From the time Oregon was declared a Territory of the United States in 1848, controversy surrounded the naming of Salem as the seat of government. Oregon City, the seat of the Provisional Government, was one of Salem’s rivals. Even after Congress confirmed Salem as Territorial capital in 1852, there was an attempt to relocate the government to Marysville (present day Corvallis.) While designation of the capital was disputed by supporters of the contending Willamette Valley settlements, the Territorial Legislature met in Salem, generally, from 1850 onward.

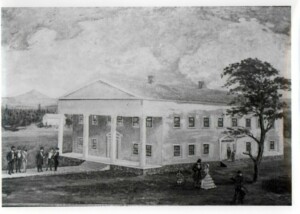

The First Capitol

Drawing by Murray Wade of the first Oregon State Capitol Building of 1855, it burned December 29. 1855 before it was occupied., WHC Collections 2004.010.0019

In 1853 the Territory entered into agreements with local contractors to erect a permanent statehouse, which was to be situated on Block 84 of Willson’s plat at the head of the long central square, or “avenue.” The partially completed building was occupied briefly by the Legislative Assembly in December, 1854. But the following year, the legislators removed to Corvallis.

Once it was learned the federal government would not authorize expenditure of monies appropriated for construction at any place but the Territorial capital designated by Congress, the legislature returned to Salem and reconvened in the statehouse.

The Capitol Fire, 1855

On the night of December 29, 1855, after having been in use scarcely a month, the frame building burned to ruins. Although arson was suspected, a formal inquiry proved that the fire was not intentionally set. Whatever the cause, the statehouse, the territorial library, and its furnishings were destroyed.

Prior to its destruction, Oregon’s first permanent statehouse had been a two-story, temple fronted building in the prevailing architectural style of the day, Greek revival. Rectangular in plan, it was oriented lengthwise, with its columned and roofed porch facing west onto the open space of Willson Avenue. While no documentary illustration was made of the building while it stood, the legislative record gives a clear enough description of its general character.

As initially planned, the statehouse was to have been constructed of smooth-dressed ashlar (building stone) and its porch was to have been formed of columns and antae, or pilasters at the ends of the main walls. A stone foundation, following this plan, was laid by Charles Bennett in 1853.

- W. Ferguson, one of the statehouse commissioners superintending construction, submitted his bill for drafting plans, specifications, and detailed drawings in December, 1853. Abruptly, in an apparent effort to stay within the limits of the appropriation of $50,000, the Legislative Assembly passed a resolution changing the material of construction to wood and the style of the Classical columns to the more simply rendered Doric style. Accordingly, Ferguson drafted new plans, drawings and specifications “in the Grecian Doric order of architecture.” The design was carried out in all but certain of the finishing details by principal contractor William H. Rector. (For example, the original plan called for a lantern, or dome, for its gable roof but this feature was never built.) Though very short lived, the territorial building had nonetheless started a classical tradition for Oregon statehouses.

Interim Meeting Spaces

For the next twenty years, which included the transition to Statehood in 1859, the Oregon Legislature convened in rented rooms in commercial buildings near the Salem riverfront. The primary locations were the Nesmith Building and the Holman Building located at the southwest and northwest corners, respectively, of the intersection of Commercial and Ferry streets. Neither building stands today.

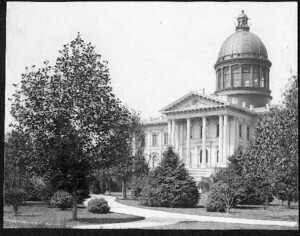

The Second Capitol

Oregon State Capital Building, front entrance. Second state capitol building, west elevation facing Willson Park. Summer photo, trees with leaves. Concrete walks in park area. Mounted on cardboard., WHC Collections 0083.001.0001.006

In 1872, the State Legislature appropriated funds to erect a new statehouse on the traditional site at the head of Willson Avenue. Construction began in 1873 and was substantially complete by 1876. The second statehouse was classically inspired but it reflected a widely revived interest in the monumental architecture of the Italian Renaissance. This building was far larger than the previous capitol. To contain all the departments of government as well as the legislature and officers of state, the building was three stories tall and shaped in the form of a cross. The long axis extended north to south the length of 264 feet. Minor arms, or projecting entrance sections were centered on the east and west fronts. Walls were constructed of brick above the ashlar (building stone) ground story of native Oregon sandstone from the Umpqua region. Upper stories were trimmed with limestone and ultimately were given a stone gray finish overall. The low, double-pitched roof had a modillion cornice, raked at north and south gable ends.

When the Salem City Council authorized vacation of Summer Street at the west front of the statehouse in 1880, the ninety-nine foot right of way became part of the capitol grounds in accordance with the Legislature’s request.

During 1887 to1888, when the grand staircases and covered porticoes supported by colossal Corinthian columns were added to the east and west entrances, it made the approach to the west front very visible. It was not until 1893, however, that the new statehouse was crowned with the dome called for in the original design by the Portland firm of Krumbein and Gilbert. Including additional appropriations for the final improvements, the new statehouse was completed at a total cost close to the original estimate of $550,000.

The copper-clad dome echoed, as did those of so many statehouses across the country, including the dome which Thomas U. Walter added to the nation’s capitol in the 1850’s. There being no other superstructure like it in Oregon, the statehouse dome became a symbol of state government.

Although symbolic, the dome’s primary purpose was to admit light to the rotunda. Owing to the structural support system required for its addition, the dome was at once the feature which most distinguished the statehouse and the principal means by which the building was destroyed after nearly sixty years of service.

The Capitol Fire, 1935

On April 25, 1935, a fire started in the basement of the east wing and quickly spread to piles of old records in wooden storage boxes. As the strong updraft in the hollow columns enclosing the dome’s eight supporting steel lattice girders pulled the flames through the rotunda to upper stories, the core of the building was rapidly engulfed in flames. The dome inverted and collapsed into its well. Despite the efforts of the Salem Fire Department, the building could not be saved. Volunteers succeeded in removing a miscellany of furniture and records. Among the rescuers of records and furniture was the young Mark O. Hatfield, who would later become Governor of Oregon and a United States Senator.

Oregon’s early capitols followed conventional patterns for the statehouses of their day. In the original capitol of the 1850’s, a simple, rectangular temple form, the upper and lower bodies of the legislature were housed in chambers on separate floors. In the statehouse of the Victorian era the House and Senate occupied chambers on opposite ends of the main story, which was the second level. The capitol of Justus Krumbein and W. G. Gilbert recalled the legislative heritage of the Roman Republic and the splendor of the Renaissance. The seal of the State of Oregon was displayed on the ceremonial west front, in the cover over the portico.

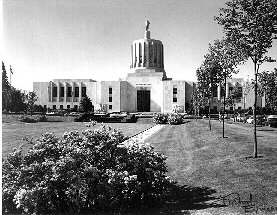

The Third Capitol

Richard O. Eymann, Photo of the present day (third) Oregon State Capital Building, front view. Photo taken by State Representative Richard O. Eymann and was hung in his office at the Capitol for years until given by him to the Marion County Democratic Central Committee in 1972, when it was bought by R. Vance MacDowell., WHC Collections 1983.031.0001.003

The next Capitol, constructed between December 4, 1936, and June 18, 1938, was designed by the New York architectural firm of Trowbridge and Livingston, in association with Francis Keally. The Portland firm of Whitehouse and Church served as Oregon associate architects, with Earl P. Newberry serving as their resident representative at the site. Ross B. Hammond was the general contractor.

Erected in the Modernistic style, this new capitol was built on a reinforced concrete foundation. The original interior structural system is a combination of reinforced concrete, steel framing, and hollow clay tile. Exteriors are clad in four to twelve inch widths of Vermont (Danby) marble above a granite base which slopes to reveal a full ground story at the south. The entire original building width approached 162 feet. The surfaces of the various capitol roof projections are predominantly flat and were originally covered with quarry tile. This material was removed in 1979, and replaced with a conventional built-up bitumen roof.

The building was sensitively enlarged in 1977 in a compatible manner by the Portland firm of Wolf, Zimmer, Gunsul, Frasca. Cleaned in 1986 and meticulously maintained, the capitol retains its original function and, as we enter the twenty-first century, is in excellent condition.

The capitol entrance faces north to the Mall, and features two adjacent (perpendicular) blocks of tree-ringed parks and gardens, bordered by arterial streets and flanked by five state office buildings occupying separate blocks. Of these, the Oregon State Library, Public Service Building, and Department of Transportation, were designed to be stylistically compatible with the capitol.

To the east and west of the capitol are two parks. Willson Park, is situated to the west and served historically as the focal point for the entrance to the original Capitol building. This park was re-designed by Lloyd Bond and Associates in 1965, following its transfer to state ownership from the City of Salem. The Columbus Day storm of 1962 eliminated most of the early plantings of evergreen trees. Capitol grounds on the east, generally known as East Park, extend from the Capitol to the Justice Department complex on the east side of Waverly Street. This complex is composed of the Supreme Court Building and the old State Office Building, both designed by William C. Knighton. East Park is distinguished by the presence of intact aspects of an early landscape design, which include trees, shrubs, and some of the sidewalks.

The cast bronze statue, “The Circuit Rider” by A. Phimister Proctor, was moved to this site after the completion of the new building. Also evident are remnants of the classical fluted columns from the old Statehouse portico, which have been arranged as an historical exhibit. To the south, the Capitol is bordered by State Street and the campus of Willamette University.

Researched and written by Paul Porter and Susan Gibby.

This article originally appeared on the original Salem Online History site and has not been updated since 2006.

Leave A Comment