Readers should feel free to use information from this article, however credit must be given to the Willamette Heritage Center and to the author.

By John Scott

Historian, Sir Martin Gilbert, writes that European Jews in the nineteenth century considered the United States a “Goldene Medina” – a Golden Realm Jewish entrepreneurial skills were needed, if not always welcomed, in the United States (more on this later). This was especially true along the frontier line where knowledgeable bankers and merchants were not in good supply. The Hirsch brothers had some training as apprentices under Bavarian merchants and brought those skills to Oregon.[2] The initial impetus in moving the brothers west was in response to the California Gold Rush of 1849. The oldest of the brothers, Leopold, came to America in 1845 and was in California by 1851. He witnessed hectic and exciting times; in the four years following the discovery of the precious metal at Sutter’s Mill California’s population jumped from 14,000 to over 223,000, and some $200,000,000 in gold was pulled from the ground.[3] The Californians were miners, but also merchants and Jews were part of this entrepreneurial pulse. Many of these businessmen made fortunes supplying goods to the miners. However, there were too many men trying to “find color” in the creeks of the Sierras, and there were too many general stores, and this propelled a scattering gold miners and goldsmiths throughout the West. Hirsch left California and journeyed to Portland where two of his brothers, J.B. and Maier, had already arrived by 1852.[4] One can surmise from correspondence between the brothers that the intense commercial competition in California spurred them to seek more opportunity in Oregon. There were however, Jewish merchants already in Portland as early as 1849. Jacob Goldsmith, Lewis May and Simon and Jacob Blumauer were some of the general merchandisers in “Stumptown” preceding the arrival of the Hirsch brothers.[5] The brothers decided to test their skills in Marion and Polk counties. Leopold, J.B. and Maier set up shop in Salem while their younger brothers, Edward and Solomon (they both arrived in 1858), established general mercantile stores, first in Dallas (1858-1861) and then Silverton (1861-1864).[6] Solomon later went on to great prominence as a politician and merchant based in Portland. He served in the Oregon State Senate and was later the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire for three years during the McKinley administration. To say that the skills of the Hirsch brothers, and of Jews in general, supplied a need within the Oregon business community is not to suggest absence of antisemitism. For example, upon their arrival in the 1850’s, the politically Republican Hirsch brothers, and other Jews, sadly, were castigated by the editor of the Oregonian, Thomas Dryer. Dryer’s prejudice may be one of the compelling reasons why the Hirsch clan moved to Salem. Dryer resented the “Jewish mercantile spirit” and as newspaper editor Harvey Scott notes: “the Oregonian then was full of sneers about the Jews. The whole merchant class, indeed was regarded with suspicion and distrust, and with consequent dislike, by the provincial pioneer mind.”[7] Regardless of the disposition represented by men like Dryer, the Jews quickly earned for themselves a position of trust and success within the Oregon business community, including Salem. The 1870 United States Census lists the following members of the Hirsch family living in Salem: Leopold Hirsch – 46, and his daughters, Rosa – 11, Lora – 10, and Sarah – 8 (Leopold’s wife, Alisse “Lizzy”, had died in 1864 at age 27); J.B. Hirsch – 42, his wife Hanah – 28, and daughter Ella; and Maier Hirsch – 40, his wife Clara – 28, and children, Ella – 5, and Isaac – 4.[8] Leopold labored as a merchant here in Salem until 1881 and died in 1892. Maier, when unhindered by business concerns, was active in the Republican Party, especially at the time of the Civil War. The Republican Party was divided during the War with the more vibrant and successful branch known as the Union Party. This party successfully saw Lincoln reelected to the presidency. Maier Hirsch was selected as a delegate from Oregon to serve in the Union Party’s national nominating convention held in Baltimore in 1864.[9] Maier lost in the election of 1870 while trying to earn the office of Oregon State Treasurer. One indicator that Maier was a man of some means is that the 1870 U.S. Census lists Tom Hoy, a twenty year old Chinese immigrant, as the cook for the Maier Hirsch family.[10] Most Salem residents could not afford to employ a cook. The 1870 census should also include Edward Hirsch (1836-1909), the most accomplished of the Salem Hirsch family. Hirsch had just finished his time as the manager of the Eagle Woolen Mills in Brownsville, returning to Salem where he married Miss Nettie Davis.[11] Edward’s career as a public servant has been surpassed by very few people in the history of Marion County. Following his work as a sales associate for his brothers, J.B. and Maier (1864-1866) and managing the mill in Brownsville, Edward worked as a partner in Herman and Hirsch, and then with his brother in the mercantile firm L & E Hirsch (1868-1878).[12] By this time Edward was a man of noble bearing and a person who worked well with other people. As a colleague described him, Hirsch was “short with heavy shoulders. He had dark piercing eyes and usually wore a dark beard [becoming gray]. He was a good mixer and had the ability of making and holding friends.”[13] These strengths, along with his acumen for making and saving money led to his 1878 nomination for Oregon State Treasurer representing the Republican Party, a post he handily won. Hirsch’s tenure as state treasurer was the longest in state history and one of the most successful.[14] When he assumed office, on September 9, 1878, the United States economy was just turning the corner following the Great Panic of 1873. Banks were on better footing and the early 1880s saw stock investments in a bull market. This was the era that historian, John Garraty, incisively calls The New Commonwealth. Fortunes were being made by those who had courage and business savvy. Two transcontinental rail lines connected Oregon to the East and to California in the 1880s. Hirsch jumped into this hot cauldron of opportunity and capitalism. He took office when the “securities of the state were at a discount.”[15] Hirsch corrected this; he instilled confidence back into the state’s finances, cut taxes – encouraging savings and investment, and saw “public credit…advanced far above par, and sustained by that confidence that gives tone and solidity to public credits.”[16] When Hirsch left office, in 1887, the state indebtedness had been almost entirely cleared, and he more than tripled the amount of investible monies of his predecessor from $112,000 to $388,000.[17] As Oregon State Treasurer, Hirsch also served on the Public Building Commission, the State Asylum Commission, the Canal and Lock Commission, and the Board of School Land Commissioners. He helped oversee the near completion of the Oregon State Capitol building (the building destroyed by fire in 1935), and the construction of the State Asylum. The State Prison was enlarged and laid out with work buildings, including a livestock barn and foundries.[18] Hirsch followed his work as State Treasurer with service on the Salem City Council and in the Oregon State Senate. As a city councilman, Hirsch represented the first ward, which was the city of Salem north of Marion Street. On the council he worked on three standing committees: ways and means, ordinances, and fire and water.[19] He was a state senator from 1891 to 1895 and served as chairman of the Senate Ways and Means Committee during his second two year term.[20] A man so capable was, not surprisingly, rewarded. President William McKinley appointed Hirsch to the office of Salem Postmaster in August of 1898, and Theodore Roosevelt awarded Hirsch a second term. The post office was upgraded by moving the Salem operations to a new location where Hirsch proceeded to streamline services, increase rural delivery routes, and successfully oversee an increase in postal revenues.[21] Edward and Nettie had seven children: Ella, Lulu, Guy, Maude, Gertrude, Maier, and Laura. The Hirsch’s resided at a number of addresses in Salem, including 437 High Street, 264 Chemeketa Street, and 200 S. Commercial Street.[22] Locations that have now gone from residential to commercial enterprises. Following Edward’s death in 1909, Nettie, and several of the unmarried daughters, moved to Portland. There is one indicator that proves Edward Hirsch was financially one of Marion County’s more successful citizens. The 1891 R.L. Polk & Co’s Salem City and Marion County Directory lists over four thousand breadwinners in the county. Many of these citizens had insufficient personal worth to have purchased property and did not pay Marion County taxes. But many hundreds of people did own land and did pay taxes. Edward Hirsch’s property was assessed at a value of $11,110. In 1891 this placed Hirsch as roughly number fifty in the county in terms of economic value when considering property holdings as a barometer of worth.[23] Leopold, J.B., Maier, Edward, and Solomon Hirsch, were part of a Jewish cultural flowering in the nineteenth century, a blossoming which was most completely realized in the Goldene Medina – America. The brothers were exemplars in business smarts, the art of selling, building up faithful clienteles, and in the application of practical business and civic knowledge; which historian Paul Johnson says made the Jews a capitalist force.[24] The Hirsch brothers had what their brethren called yihus; they were men of status, scions from an accomplished family, and had the business and societal standing which proved their success.[25] Mark Twain once observed the difference between the right word, and almost the right word, is the difference between lightning and the lightning bug. What is the right word to summarize the skills and civic contributions of the Hirsch brothers? It is hard to settle on just one word. Perhaps capable, whose roots in the Greek language go back to the idea of having hold of something and being able to drink it down, will do for now.[26] [1] Sir Martin Gilbert, The Jews in the Twentieth Century: And Illustrated History (New York: Schoken, 2001), 30. [2] Portrait and Biographical Record of the Willamette Valley, Oregon, Illustrated (Chicago: Chapman Publishing Company, 1903), 495. [3] T.H. Watkins, Gold and Silver in the West; the Illustrated History of an American Dream (New York: Bonanza Books, 1971), 40. [4] Steven Lowenstein, The Jews in Oregon: 1850-1950 (Portland: Jewish Historical Society, 1987), 7. [5] Lowenstein, 7. [6] Portrait and Biographical Record of the Willamette Valley. 495, 496 [7] Harvey W. Scott, The History of the Oregon Country. Compiled by Leslie M. Scott (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1924), 257, 258. [8] United States Census Bureau – 1870. Records of the Marion County Historical Society. [9] Charles Henry Carey, History of Oregon (Chicago-Portland: The Pioneer Historical Publishing Co, 1992), 651. [10] United States Census Bureau – 1870. Records of the Marion County Historical Society. [11] Portrait and Biographical Record of the Willamette Valley, 496. [12] History of the Pacific Northwest: Oregon and Washington, Volume II, (Portland: North Pacific History Company, 1889), 378. [13] Fred Lockley, “Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man.” The Oregon Journal, August 1, 1930. Oregon State Library. [14] E. Kimbark MacColl, “Eight Unique Contributions to Oregon Public Life” (Lecture, Oregon Jewish Museum Group, Portland, OR, July 23, 1992) 12. Oregon Historical Society Library, MS 2440. [15] History of the Pacific Northwest: Oregon and Washington. Volume II. 378. [16] Ibid, 379. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid, 379. [19] Ibid, 378. [20] Salem City and Marion County Directory: 1889-1890. Volume 1. (Portland: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1889), 19. [21] Portrait and Biographical Record of the Willamette Valley. 496. [22] R.L. Polk & Co’s Salem City and Marion County Directory-1896. (Portland: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1896), 62. [23] Ibid, 179. [24] Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1987), 285-287. [25] Lowenstein, 74. [26] Webster’s New World Dictionary. Third College Edition. (New York: Webster’s New World, 1988), 207, 618

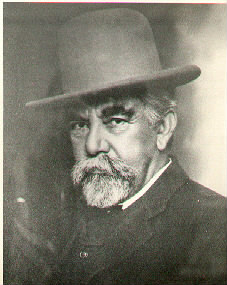

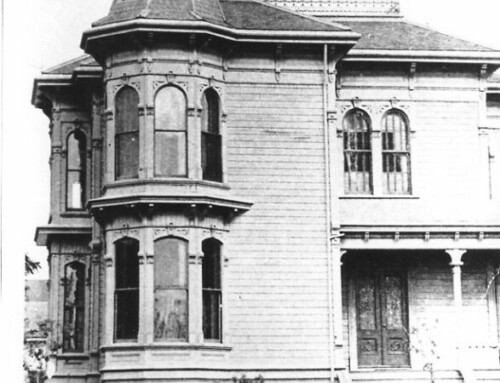

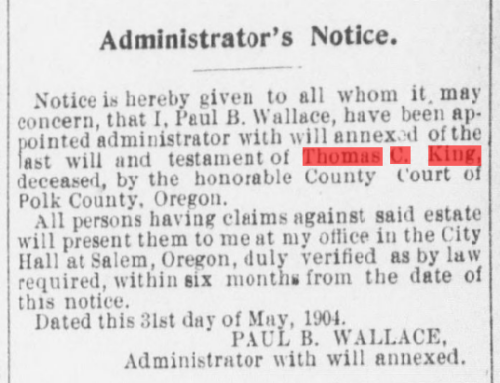

Leave A Comment